|

|

|

|

|

Regimental History

On July 13, 1865, I. N. Haynie, the Adjutant General of Illinois (successor to the wartime adjutant general Allen C. Fuller) sent a circular to the officers of all Illinois regiments, saying that the Illinois regiments were being broken up, "to be known to the future only by the history of their great achievements." He went on, "I have deemed it my duty to call upon the officers who commanded them to render me whatever aid they can to secure beyond question, for all time, a truthful record of their deeds... now when the events of the past four years are fresh in the memory of those most conspicuous in the Union cause." To that end he ordered, "You will immediately forward to this office a brief, compact history of your command... embodying in the statement all the engagements, marches and movements, with all items of interest which will give the organization a merited and enduring record in the archives of Illinois" (Adjutant General Report, 120).

These compact histories were written generally by officers of the regiment but these regimental historians are usually unnamed and unknown. The Adjutant General Office's history of the Twenty-Seventh Illinois was written by William A. Schmitt, Captain of Company A, then major, lieutenant colonel, and colonel; we know that because Schmitt's history was also published as a separate booklet. We cannot determine who wrote the A.G.O. history of the Fifty-First Illinois; it is matter-of-fact in tone like Bradley's other writing; however, Bradley resigned his volunteer commission as brigadier general in June, 1865. James Boyd (the last promoted but never mustered colonel of the regiment) was the only field-and-staff officer of long-standing at regimental headquarters after July 1865, and, after being wounded at Stone's River, Boyd had been with the provost-marshall's office in Nashville until sometime in Spring 1865. Raymond had resigned; Davis was still recovering from severe Missionary Ridge wounds; McWilliams had left the regiment in March after his exchange and release from Confederate prison; Rose was gone after resigning for disability reasons; Moody was killed at Chickamauga, Bellows at Missionary Ridge, Hall at Kennesaw Mountain; Tilton, who had de facto command of the regiment throughout the last half of 1864 until he was wounded at Franklin, had resigned and was off searching for his brother who was lost in Andersonville; that left only James Boyd actively serving—and Merritt B. Atwater, senior among the captains. Adjutant General Haynie stated in mid-July that he had sent out forms to all the regiments: "This circular, with blanks to be filled and returned to this office, has been sent to all commanding officers of troops of this state, out as well as in the service, whose address was known" (First Edition, Volume 1, p. 89).

The AGO history of the Fifty-First is quite, if not utterly, accurate. William Edward Henry of these pages, in the itinerary of Private Edward Tabler of the Fifty-First, points out that the regiment crossed the Chattanooga Creek on September 22, 1863, not Chickamauga Creek as the A.G.O. history says. In December, 1863, as the Fifty-First and other regiments hurried to East Tennessee to support Burnside, the Fifty-First moved to Blaine's Crossroads near Knoxville - by rail, according to the A.G.O. history, but actually covering the last ten miles on foot, as Tabler wrote in his diary.

The A.G.O. history does not go beyond perfunctory recounting of the regiment's movements, casualties, and unit assignments in the Armies of the Mississippi and of the Cumberland - except to class Chaplain Raymond as a "venerable and good man" and to remember being in "the thickest of the fight" at Stones River (as the regiment was a number of other places).

The exact verbiage of the A.G.O. regimental history, in italicized paragraphs, forms the framework of a fuller history of the Fifty-First Illinois. The fuller history is a progressive work, building out the framework, here, then there, then here again. The building does not necessarily proceed from beginning to end, rather from interest and material to interest and material. Initially, the history will only in sections go beyond the AGO-perfunctory, but, if you return to the site periodically, you will find this historical presentation growing - old sections stouter and cushier and new sections starting to take shape, more dependent on letters, diaries, and newspaper accounts, and integrated with information from the National Archives and the venerable, coy Official Records.

Go to top of page

AGO: The Fifty-first Infantry Illinois Volunteers was organized at Camp Douglas, Chicago, Illinois, December 24, 1861, by Colonel Gilbert W. Cumming.

Organization of the Regiment: "The officers are all military men."

[This section created March 25, 2006; last updated December, 2008; written by Leigh Allen]

The men who became officers of the Fifty-First Illinois were engaged in Illinois militia activities, building and training companies and regiments, months before the Fifty-First was constituted. Goodspeed and Healy (1909, p. 439) wrote that John Loomis and Luther P. Bradley formed "a crack Zouave regiment" in April of 1861, "crack" presumably in the sense that its unison in drill was flashy. Loomis and Bradley turned their efforts from Zouave drill to other volunteer military undertakings. (Loomis eventually went on to be colonel of the Twenty-Six Illinois.) Bradley's energies soon - at the time of Lincoln's call for 75,000 three-month recruits - turned to forming a company to be offered for service in response to that call. The company was comprised of young Chicago men, according to Alexander McClurg, who was one of the company's members, many of whom had college educations and had been "somewhat delicately reared" and hoped to "tone down some of the asperities of the private soldier's life". Luther Bradley was captain of the company which became "before long a very creditably drilled military organization, and was known as Company D, 60th Regiment Illinois Militia." The company was not accepted into Federal military service because Illinois quotas were soon full. Company D was detailed as the guard of honor while Stephen Douglas lay in state in Chicago in June 1861 (McClurg, pp. 101-105) and continued a kind of existence though members were continually departing to serve in regiments bound for "the field". (Company D reconvened in late 1863, after Bradley was wounded at Chickamauga and partially recovered, for an evening of feasting, toasting and speech-making in Bradley's honor at a Chicago hotel.)

In August, 1861, several Illinois militia initiatives were consolidated as the First Regiment, Illinois State Militia. That militia unit never got beyond an inchoate state of organization; it did however form the core of the Fifty-First Illinois. Some of the captains and "home companies" of the First Illinois Militia became the captains and companies of the volunteer regiment

(Captain Rufus Rose, Fremont Fencibles, Company K;

Captain Henry F. Wescott, Union Railroad Guard, Company A;

Captain John G. McWilliams, Sturges Light Guard, Company E;

Captain George H. Wentz, Higgins Light Guard, Company G;

Captain Theodore Brown, Scammon Light Infantry, Company D;

Captain Isaac Gardner, Tucker Light Guard, Company B). There were other militia companies that were initially, briefly, part of the new regiment but subsequently went elsewhere—either disbanding or being folded into other new regiments—the Bryan Light Guard under James Heffernan,, the Anderson Rifles under A. L. Hale, and the Yates Light Guard under William P. White.

The Fifty-First was formally constituted by Order No. 197 of the Illinois Adjutant General issued on September 20, 1861 (Andreas II, 1884-86, p. 215).

The regiment went into camp in Chicago on October 8, 1861 near what was becoming Camp Douglas [map, sketch, details]. The camp was not a war-ready barracks and training ground carved out of the near-south side of Chicago. It was a piece of prairie, four miles south of the city, called "Cottage Grove", which lay at the end of the street-car line. The line did not even continue far enough through the trees and grasses to reach present-day Hyde Park. The cars themselves were more aptly called "horse cars", for this was prior to the first steam streetcars. The Chicago Times reported once during the war, March 21, 1864, that the State Street car bound for Cottage Grove found its way blocked by a herd of cattle. The street car was halted, as the herd, occupying the entire width of the street, "presented a bold front, or rather rear, to dispute the further passage of the car." This was not yet Chicago urban living at its most urbane.

Cottage Grove was beautifully wooded and was home to several music pavilions and a large beer garden. It was popular with the German-American population who traveled the street cars to have picnics and parties. (There were other such celebration groves around Chicago; the Fifty-First reassembled, after its veteran furlough in 1864, at Wright's Grove-Camp Webb-Camp Fry on the north side of Chicago). Before Camp Douglas was ready to accept troopsóeven before it was plannedóIllinois recruits camped and trained in Cottage Grove along Cottage Grove Avenue, which connected north to the city. There were several camps, some utterly temporary, some with permanent barracks, in the Cottage Grove areaóCamp Long, Camp Blum, Camp Heckeróbefore Camp Douglas was built in late 1861; there was even a temporary Camp Douglas, which lay to the south of where the permanent Camp Douglas was built (Karamanski, 1993, p. 78). The Forty-Second Illinois Infantry left Chicago for the field before they ever moved out of the Grove into the Camp. Even after Camp Douglas was completed and fully functioning, the housing and training of regiments at at the camp was not confined to the walls which surrounded it. William Bross wrote, "...troops were cared for in and about Camp Douglas, for it will be remembered at times the section west of the camp and nearly to State Street and south, far away toward Hyde Park, were covered with camps and open spaces for drilling the troops" (Bross, 1878, p. 170). Elias Colbert, a Chicago newspaper editor, remembered "the novel sight of tents dotted all over the surrounding region as far as the eye could reach" (p. 94).

The Fifty-First Illinois was one of the first to inhabit the new camp and undergo its outfitting and first training there, moving in while it was still being built. Benjamin Smith of the Fifty-First wrote that, after his company arrived in Chicago, supped at the Lloyd House, overnighted at the monstrous "Wigwam" (the ramshackle, quick-built, wooden auditorium where the Republican convention of 1860 nominated Abraham Lincoln), and breakfasted, again at the Lloyd House, they boarded "street cars" for Cottage Grove (Smith, p. 12, Cook, p. 38), and so began their military careers. Albert Tilton of the Fifty-First wrote home on October 12, 1861, "We are encamped at Cottage Grove, about 4 miles south of Chicago but easy of access by street car. Extensive and comfortable barracks are being built which when completed are calculated to accommodate 4 regiments of 1200 men each." Even though the Camp Douglas barracks were just then under construction, Tilton headed his letter "Camp Douglas 51st Ill". Tilton's letter of November 9, 1861, headed "Camp Douglas Chicago Legion (51st Ill)", wrote "...we have as yet no stoves put up in our barracks".

The regiment shuffled through several identities before it went to the field of war. At inception it was envisioned as one of the four regiments of a planned Douglas Brigade, a brigade of regiments formed in Illinois' northern military district, constructed by the war-footing military reorganization of 1861, and named in honor of Stephen Douglas, who had died in June, 1861. Two other of the regiments of this to-be brigade were the Forty-Second Illinois Infantry and the Fifty-Fifth Illinois Infantry. There was never a fourth regiment for the phantom Douglas brigade, even on paper, and the brigade ceased to exist before it started. The men of the Fifty-First, however, at some point after arriving in Chicago became aware that the regiment was designated as a constituent of the Douglas Brigade; they felt a certain gratification in membership in a brigade named after the great Stephen Douglas, greater for having thrown himself into the war effort after his election defeat and then, especially, having died. There was at least a passing notoriety to being members of this named brigade. Tilton wrote, in a letter of December 10, 1861, "The 2d Regt [Fifty-Fifth Illinois] Douglas Brigade left for St. Louis yesterday. We are the 3d Regt of the Brigade... It will be a splendid brigade." Benjamin Smith noted the Fifty-First's being part of the Douglas Brigade in his entry of October 11, but Smith sometimes backed into his dates, and not always correctly. The Fifty-Fifth Illinois trained at Camp Douglas but left for the field before the Fifty-First did, and the two regiments never served together. The Chicago Tribune said the Fifty-Fifth was "well known as the Second Douglas"; The Fifty-First was never known as the "Third Douglas". The Forty-Second, which was the first-formed regiment of the Douglas Brigade (but seldom called the "First Douglas") and which also assembled in Chicago but two months earlier than the Fifty-First, always served together with the Fifty-First.

The Chicago papers in 1861 and early 1862 referred to regiment as the "Chicago Legion" or the "Ryan Life Guard". The name "Ryan Life Guard" never gained currency, but the early stationery of the regiment, early Illinois newspaper accounts, and the early self-reference of its officers identified the regiment as the "Chicago Legion", legion because in contemporary military parlance a legion consisted not only of infantry units but also of cavalry and artillery units. The Adjutant-General's Order No. 197 of September 20, which formally organized the regiment and called it specifically the "Chicago Legion", stipulated, "There may be attached to said Regiment one company of Cavalry and one company of Light Artillery - said companies to be raised by voluntary enlistment for said purpose, and not to be selected from any of the companies of cavalry or artillery heretofore reported and accepted by the state." Albert Tilton glossed "legion" in the terms of a new soldier, "The 51st Reg is to be composed of 10 Companies of which 8 are to be Light Infantry, 1 of Flying Artillery & 1 Cavalry Co. making in itself a small brigade able to act on the offensive & defensive" (letter of October 12, 1861). For a time Allen Waterhouse's battery and Charles Roland's cavalry company were constituents of the regiment. On October 30, 1861, the Fifty-First Illinois counted six infantry companies and the battery. The battery accounted for 47 of the 296 men who had signed with the regiment as of that date.

As late as November 14, 1861 Colonel Gilbert Cumming authorized cavalry recruitment for the regiment.

Subsequently, however, Illinois Adjutant-General Fuller cooled toward the "legion" concept and reassigned the cavalry and artillery units. This was a major setback to recruiting efforts as the battery men and the cavalry troopers comprised one fifth of the regiment's strength. The adjutant general said that he would assign two infantry companies to the regiment, but he did not do so.

The regiment was left with only eight companies of infantry, rather than the usual ten; hence when the regiment went to the field in February, 1862, it consisted only of 684 enlisted men. (Not until July 1862 did the regiment gain a Company F, and not until Spring 1865, after the regiment had fought its last fight, did it gain a Company I.)

Through the end of February 1862, the regiment had its lieutenants scattered through Illinois recruiting to fill up the various companies. At Camp Douglas contingents of independently recruited men were added to existing companies, as when Albert Eads' Knox County contigent became the final piece of Captain Nathaniel Petts' Iroquois County company (ultimately Company C). Eads thus earned the second lieutenant's office of Petts' Company. Whole companies were similarly added to the regiment. John Whitson recruited sixty men in Rock Island County. Those sixty men were joined by William Greenwood's twenty-plus men (after considerable negotiating). These two contingents eventually became Company H of the Fifty-First. Whitson was captain; Greenwood was first lieutenant. Thus the Fifty-First built itself; its regimental existence was not a foregone conclusion. The "Rock Island Regiment" that was forming at the same time under "Colonel" Waters McChesney, and which had grown to over 200 men by the time it reached Camp Douglas, was cut into pieces and the pieces assigned to other forming regiments.

The Fifty-First Illinois was the "Chicago" Legion because the majority of the officers were recruited from Chicago and because the regiment mustered in in Chicago. Only two companies, C and H, had no Chicago-commissioned officers (Kirkland I, 1895, p. 162). There was yet another reason why very practically the regiment's closest ties were to Chicago: Luther P. Bradley was the first Lieutenant Colonel of the regiment. Before the war he worked for the firm of Munson & Bradley. Francis Munson's downtown store at 140 Lake Street became the local point of contact for the regiment. Letters and packages could be dropped off there for (relatively) quick transport to the regiment in the field. The first set of colors made for the regiment was initially on display there, and Munson carried the flags to the regiment in the field at Farmington, Mississippi. When one of the regimental flags came back to Chicago, in shreds, after the Battle of Chickamauga, it was on display at Munson & Bradley's. The Chicago connection was more than officer-deep; Companies A, G, and K drew the majority of their privates from the City of Chicago and the Counties of Cook and Lake. When the regiment departed Chicago in February 1862, The Chicago Tribune bid the Fifty-First good-bye "...with peculiar feelings. Composed, as the rank and file is, mainly of our own citizens, and citizens who have occupied prominent and humble positions in this community, it is severing a near tie to say farewell and leave them to the uncertaintities of war. Chicago will watch the future course of this regiment with peculiar pride, and will anxiously await the day when they shall return..."

Governor Richard Yates appointed Gilbert W. Cumming,

a New York native and Chicago attorney, as colonel of the regiment. Cumming was a man of some military training but little military experience. He was born in New York in 1817. At the age of 16 Cumming enlisted in an independent military company, submitted to all its training and discipline, and eventually rose to command of a regiment in the New York militia whose only public function was in composing the public unrest relative to the rising of Anti-Renters in his corner of New York. He rose to the colonelcy of the militia regiment, a position which he held for six years. In the 1850s Cumming migrated first to Wisconsin, then to Chicago, where he established a successful law practice.

The first Lieutenant Colonel of the Fifty-First Luther P. Bradley also had some military background. Bradley was born in 1822 in Connecticut, and his initial military training came with the Connecticut militia before he migrated to Chicago in 1855. There, he was employed with the firm of F. Munson, stationers and booksellers. Bradley accepted a captain's commission with Company D of the First Illinois State Militia.

Samuel B. Raymond, the first major of the Fifty-First (and later lieutenant colonel commanding the regiment) was born in New York and came to Chicago where he was engaged first in printing, then "mercantile pursuits", then insurance. He was actively engaged in militia activities, serving as lieutenant colonel of the First Illinois State Militia. His father Lewis Raymond was chaplain of the regiment; a younger brother Eugene was a private in Company K. Regimental Adjutant Charles W. Davis was a native of Concord, Massachusetts and had served in the state militia for five years before migrating to Chicago in 1854.

For better or worse there were no Westpoint graduates among the officers of the regiment, but the officers of the regiment did not themselves require basic military training. They had that. Colonel Cumming wrote to Captain Nathaniel Petts, selling him on joining his independent infantry company to the regiment, "The officers are all military men and the regiment will be equipped in the best manner." The organizers of the regiment and its field officers took satisfaction that the regiment was not officered by political appointees - who might be marvelous creatures of patronage in the city but inept commanders in the field.

The Chicago Tribune wrote of the regiment, "In point of drill it is superior to any regiment that has been at Camp Douglas this winter." Camp Douglas was new, and not a lot of regiments had trained there; still, the Fifty-First was in camp a relatively long period of time, four months, before going to the field. And, its days were consumed with drilling, and more drilling. The Federal command heirarchy was frightened by what became of its untrained regiments at Bull Run. "With the establishment of Camp Douglas, troops were, for the first time, given uniform instruction in bayonet and close-order drill. The state appointed two former Ellsworth Zouaves as the official instructors at Camp Douglas. [Camp Commandant] Tucker established a schedule that gave the recruits at least four hours of drill each day." (Karamanski, p, 84). Tilton wrote home about the Fifty-First's training schedule. "We 'turn out' at day break, breakfast at 7, drill from 9 to 11, dine at noon, drill from 2 to 4 PM, take supper at 5 & go to bed at 9 1/2." The diary of Edward Tabler for January 1862 gives some of the tiny permutations of becoming a soldier at Camp Douglas, "Drilling again today, as usual, and learning to be a soldier - Drilled again, at the usual hour, and done well - Drilling again, and have a bad cold - Drilling again - Drill a little while again, but don't feel very well - The boys went to the lake shore, and fired their guns at a target - Drill again today, and have Dress Parade - The boys drilling by themselves today. We done well." The Fifty-Sixth Illinois Infantry, in contrast, found itself in the field after a much shorter interval in camp, and training was not an ambition of its field officers. Chaplain David Bunn wrote in his diary on May 3, as the Fifty-Sixth was joining General Pope's army for the war on Corinth (which came to be known as the "Siege of Corinth"), "The discipline of the Regt. is sadly deficient, and seems to lack a head to make it what it ought to be. The Col. has never yet said 'Shoulder arms' to the Regt." Quartermaster William Ferry of the Fourteenth Michigan, trying to move men and materiel away from Hamburg Landing in May 1862, complained of his regiment, "There is no discipline for this or anything else among our officers." A New York officer criticized the command style of his fellows, "Their orders come out slow and drawling, then they wait patiently to see them half-obeyed in a laggard manner." The militia careers and ambitions of the Fifty-First's field officers and some of its captains propelled the regiment past such inexperience and growing pains. Its field officers, for better or worse, had a taste for command - and some experience in exercising it. Ferry of the Fourteenth Michigan wrote, as his regiment got close to its first fighting, "The result of fight must prove disastrous to this regiment solely for the want of discipline & trained obedience to orders." Even when still untested, the Fifty-First had confidence in its training and proficiency in drill. Time would tell.

In October at Camp Douglas, the men of the regiment began receiving uniforms and some equipment, "So that", as Adjutant Charles Davis put it, "we hope to make soldiers of our men in very short time." The regiment was not exactly "equipped in the best manner", as Colonel Cumming promised Petts, not at first. Benjamin Smith, a private of Company C, wrote that Quartermaster Howland, judging by the ill-fitting uniforms that were issued at Camp Douglas, "must have had the mistaken impression that he was clothing a company of giants."

REFERENCES FOR THIS SECTION:

Cumming to Captain Nathaniel Petts, September 25, 1861, Fifty-First Illinois Regimental Books 3, Record Group 94, National Archives and Records Administration. The company Petts raised became Company C of the Fifty-First Illinois.

Davis to Lt. Northerington, October 7, 1861, Fifty-First Illinois Regimental Books 3, Record Group 94, National Archives and Records Administration.

The Chicago Evening Journal.

The Chicago Times.

The Chicago Tribune.

James Grant Wilson, Biographical Sketches of Illinois Officers Engaged in the War Against the Rebellion of 1861. Chicago: James Barnet, 1862.

A[lfred]. T. Andreas, History of Chicago from the Earliest Period to the Present Time, 3 volumes. Chicago: A. T. Andreas, 1884-86

Benjamin Smith, Private Smith's Journal, Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1963.

David P. Bunn Diary, SC 209, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, Springfield, Illinois.

William M. Ferry, Jr. to wife, dated "Between Hamburg & Corinth, six miles out, May 1st/62"; William M. Ferry, Jr. to wife, dated "In camp near Farmington which is 4 miles from Corinth May 5th/62", William Montagu Ferry Family Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Reid Mitchell, The Vacant Chair: The Northern Soldier Leaves Home, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 24 (slow and drawling orders).

Moses Kirkland, History of Chicago, Illinois, Two volumes. Chicago: Munsell & Co., 1895, Vol. 1, p. 162.

William Bross, "History of Camp Douglas," Paper Read before the Chicago Historial Society, June 18, 1878, in Mabel McIlvaine, ed., Reminiscences of Chicago during the Civil War, New York: The Citadel Press, 1967 (originally published in 1914), 160-194.

Alexander C. McClurg, "American Volunteer Soldier", Extract from an Unpublished Memoir, in Mabel McIlvaine, Reminiscences of Chicago during the Civil War, New York: The Citadel Press, 1967, (originally published 1914), 97-150.

Weston A. Goodspeed and Daniel D. Healy, History of Cook County, Illinois: Being a General Survey of Cook County History including a Condensed History of Chicago and a Special Account of Districts outside the City Limits from the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time, Chicago: Goodspeed Historical Association, 1909.

Theodore J. Karamanski, Rally 'Round the Flag: Chicago and the Civil War, Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers, 1993.

E[lias] Colbert, Chicago: Historical and Statistical Sketch of the Garden City, Chicago: P. T. Sherlock, 1868.

Frederick Francis Cook, Bygone Days in Chicago: Recollections of the "Garden City" of the Sixties, Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1910.

Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois: Containing Reports for the Years 1861-66, revised by Jasper N. Reece, Springfield: Phillips Bros., 1900-02.

Go to top of page

AGO: February 14, 1862, ordered to Cairo, Illinois. Moved to Camp Cullum, on the Kentucky shore, on the 27th. On the 4th of March moved to Bertrand, Missouri, and on the 7th moved to Sykeston, and to New Madrid, and 10th, assigned to the Division of Brigadier General E. A. Paine, and Second Brigade, consisting of Twenty-second Illinois Infantry, and Fifty-first, Colonel Cumming commanding. On the 13th, made a reconnaissance in force, and, 14th, New Madrid was evacuated by the enemy.

To the Field: Cairo to New Madrid.

Section created July 21, 2006; written by Leigh Allen.

Even as the regiment took the field, Colonel Cumming was still trying to bring his regiment up to full strength by the addition of another two companies. He authorized John W. Campion to raise a company in the central Illinois town of Bloomington, McLean County. From February 21 to March 7, 1862, an ad ran in the Bloomington Daily Pantagraph; it read, "Col. Cumming's Regiment. - J. W. Campion has received authority to raise a company for the 51st regiment Ill. Volunteers. Any persons wishing to enlist will find this a crack regiment to go in, and will soon see service."

Campion had considerable success in recruiting men for his company. He recruited 50 men, then formed a partnership with Sylvester G. Parker, a farmer of means, to continue recruiting while he took the first recruits to Camp Dubois (Anna, Illinios, Union County) to begin their outfitting and training. A company skirmish broke out. While Campion was away, Parker held an election for the captaincy and won. On his return, Campion withdrew his men and formed another company. So said Campion. Parker said that Campion was present at the election on March 22 but received only 32 votes against 57 for Parker. Campion then, miffed, went off with 32 men and began to fill out another company. Parker said his 83 men were mustered in as Company H of the Sixty-Third Illinois on April 21 but that Campion's unit was not. Adjutant General records give the lie to this contention of Parker's for both companies were mustered into the Sixty-Third Illinois on the same day, Campion's Company D weighted with men from Bloomington, McLean County, Parker's Company H with men from Decatur, Macon County.

In the upshot, the Fifty-First Illinois did not gain a company from Campion's promising initial efforts. By the time the Campion's company was mustered in, the Fifty-First was on board a steamship heading for Fort Pillow, though certainly a company could join the regiment in the field (as did Company F a few months later). There is a more likely explanation than mere distance for Campion shopping his wares elsewhere. All the companies of the Sixty-Third were raised in central and southern Illinois and such local affinities were effective in a way that potentional ties to a "Chicago" legion could not be. The opportunity for satisfactory outfitting and thorough training were greater at Camp Dubois than they were with the Fifty-First Illinois as it boated up and down the rivers and then debarked in Tennessee and marched for Mississippi in April and May, 1862.

AGO: April 7, moved against Island No. 10; 8th, pursued the enemy, compelling the surrender of General Mackall, and 4,000 prisoners; 9th, returned to New Madrid; 11th, embarked and proceeded down Mississippi to Osceola, Arkansas; 17th, moved toward Hamburg Landing, Tennessee, disembarking 22d. April 24, the Brigade of Brigadier General John M. Palmer, Twenty-second, Twenty-seventh, Forty-second and Fifty-first Illinois, and Company C, First Illinois Artillery, Captain Hightailing [Houghtaling], known as the "Illinois Brigade," was assigned to Brigadier General Paine's Division. Engaged in the battle at Farmington, and siege of Corinth. Just previous to the evacuation of Corinth, the Army of the Mississippi was organized into two wings and centre. The Division of Paine and Stanley, constituting Right Wing, under Brigadier General W. S. Rosecrans.

From Island No. 10 to Hamburg Landing, Tennessee, April 1862

At Island No. 10, among Pope's men, there was euphoria at the ease of the victory, the haul of equipment, and the numbers of prisoners. Charles Davis, the major of the Fifty-First Illinois, wrote later: "At the scene of the victory, the excitement during the 7th was intense...The next day the joy over the surrender was unbounded." Major General John Pope was popular with the nation and embraced by the press. The nearly bloodless capture of New Madrid and Island No. 10 was seized upon by the press and the population in the North as evidence of the progress and prowess of Northern arms—unmixed good news to consider along with the troubling news from Pittsburg Landing and the Battle of Shiloh.

The Fort Pillow Mission. The next river mission for Pope's 20,000-man Army of the Mississippi was to lay siege to Fort Pillow on the Mississippi in mid-Tennessee, 90 miles south. The capture of Fort Pillow would deny use of the upper Mississippi to Confederate purposes and would bring Federal units in behind Confederate forces that held Memphis, Tennessee and Corinth, Mississippi. The shining object of the Federal campaign in the West in the Spring of 1862 was the Corinth railroad junction of the Memphis and Charleston and XX railroads ... The objective of capturing Fort Pillow was control of a greater chunk of the Mississippi Valley—and also Corinth. Memphis was 100 miles to the west of Corinth and was protected on its backside by Fort Pillow and other river fortifications. The fall of Pillow almost certainly would mean the capture of Memphis. Everyone was on this same page. Henry Halleck, who was in the process of taking command of all the armies in the west, wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton when Island No. 10 fell, "I am now of opinion that General Pope, by moving on Memphis, will produce a powerful diversion in favor of our attack on Corinth, and I shall therefore have transports prepared to

move General Pope's army down the river, changing its destination to the Tennessee, if I find it necessary on my arrival there" (Official Records 10/2, XX). At the same juncture, novice Assistant Secretary of War Thomas A. Scott informed Stanton, "If transportation arrives to-morrow or next day we shall have Memphis within

ten days, and General Pope can co-operate with General Grant at

Corinth in wiping out secession" (Official Records 8, 676).

Navy-side, Commodore Andrew Foote told Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that he understood "our object then," at the capture of Island No. 10, "was to

proceed to Memphis immediately" (p. 8).

In the Fort Pillow road-to-Memphis undertaking, as at New Madrid and Island No. 10, Pope's army would make common cause with Commodore Foote's "flotilla, consisting of gun, mortar boats, tugs, towboats, and transports" (Official Records [Navies] 23, 3). Foote had eight gunboats—seven of them were iron-clad, one was made of wood—and sixteen mortarboats. The numerous tugs and towboats were to push and pull the heavy, cumbersome gunboats and mortarboats around—and to serve reconnoitering functions. Foote's flagship was the "Benton." Foote himself, already a lauded protagonist of Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, New Madrid, and Island No. 10, had a reputation among the men. William Onstot of the Twenty-Seventh Illinois wrote home, "Com. Foote you know is one of those peculiar men who is sure he is right and then goes ahead. Consequently we may never despair of success when he is in the lead."

James Eads, who himself had an illustrious career as supplier to the western navy during the Civil War, wrote of Foote, "The Admiral was a great sufferer from sick headache. I remember visiting him in his room at the Planters' House in St. Louis, a day or two after the battle of Belmont, when he was suffering very severely from one of these attacks, which lasted two days. He was one of the most fascinating men in company that I have ever met, being full of anecdote, and having a graceful, easy flow of language. He was likewise, ordinarily, one of the most amiable-looking of men; but when angered, as I once saw him, his face impressed me as being most savage and demoniacal, and I can imagine that at the head of a column or in an attack he would have been invincible. Some idea of the moral influence that he possessed over men may be gained from the fact that, long before the war when commanding the United States fleet of three vessels in Chinese waters, he converted every officer and man in the fleet to the principles of temperance, and he had every one of them sign the pledge."

Foote had been wounded at Fort Donelson in mid-February and still was suffering acutely from the wound.

A fleet of thirty river steamboats was ready to carry Pope's men and the mission's supplies. These transports were commercial steamers. The government in one of its branches had contracted with steamship companies for their use. Pope wrote, years later, that most of the boats were supplied by an "Old Captain White," who both owned the boats and served as captain on the river. Mid-sized steamers, like the "Daniel G. Taylor," could carry a full fully filled out regiment or a small regiment like the Fifty-First along with other units or pieces of other units; larger steamers like the "Hannibal City" or the "City of Alton" could carry two regiments or more, upwards of 1500 men, even more. Regiments were shuffled about, consolidated with others, or broken up to fill out the steamer spaces. John Greenman of the Eighth Wisconsin Infantry wrote, "My company and one other company of our reg't and two companies of cavalry were ordered on this boat (Steamer Sam Gatz)... six companies of our reg't were on Steamer McClellan, and the other two companies on the Steamer Spread Eagle."

The Steamboat City of Alton, in elegance of appointments, was fit to carry the governors of states. Captain William Stewart of the Eleventh Missouri said the regiment was headquartered on board "a fine boat 'Hannibal City'." The soldier passengers on the Steamboat Admiral, on the other hand, referred to it as "an old tub." At least one of the steamboats had been captured from Confederate forces. Pope's flagship was the Steamboat J. D. Perry; the several companies of the U. S. Regular Cavalry which were attached to the Army of the Mississippi traveled on the Perry with Pope.

Down the Mississippi. The men of the Army of the Mississippi expected to have a few days to rest on their Island No. 10 laurels, but in the evening of April 11, the Fifty-First Illinois and other regiments received orders to break camp and move quickly to the river to embark on steamer transports. John Campbell of the Fifth Iowa wrote in his diary, "We have orders to get ready to march. I put on a clean shirt." There was urgency to the order; they were to be off even that night. Charles Wills of the Seventh Illinois Cavalry wrote to his brother, "I think that Pope's hurry is caused by his fear that Grant and company will reach Memphis before him." The Fifty-First pulled up stakes and marched several miles through rain and mud to their assigned point of embarkation. But the rain delayed the start of the river mission. Otis Moody of Company K wrote, "It has now grown into a proverb, that stormy weather & the 51st always go together." The regiment, like others, spent the rainy night in a makeshift camp in a muddy corn field on the bank of the river. John Hill Ferguson of the Tenth Illinois infantry wrote in his diary that the Tenth pitched tents in a corn field and carried off fence rails "in less than no time to make some fires to cook - we cut corn stalks to make our beds - altho' they were wet they kept us out of the mud. It continued to rain all night." Charles Wills of the Seventh Illinois Cavalry wrote, "The rain has been falling in torrents... you can imagine the time we had pitching tents in a cornfield" (p. 81).

On April 12 the Fort Pillow expedition got underway. Commodore Foote's gunboats and mortarboats started down the Mississippi at about noon. Steamers tied up at stipulated points along the river shore below New Madrid. Throughout the afternoon and evening the steamers took on soldier-passengers, cavalry horses, artillery guns, ammunition, and other cargoes. William Pittenger of the 39th Ohio wrote from the "Admiral" at 8:00 p.m., "Are now all aboard. There are 12 steamers here loading." Hall wrote, "Our boat didn't report till after sundown and we had a tough time loading without any moon." The correspondent of The Chicago Tribune described the evening scene: "All along the river bank the watch fires gleamed brightly until they dwindled into stars at distant Point Pleasant. Drums were beating and fifes shrieking. Regiments were leaving quarters and embarking on transports. Many of the transports were already laden down to their guards with soldiers, wagons, ambulances, horses and commisary stores. [Soldiers] were lying upon deck wrapped in their blankets; some chatting and smoking; here a group singing, and there another intently engaged at cards" (Report dated April 12, 1862; edition of April 17, 1862).

Toward 11:00 p.m. the first transports cast off and headed down the river. It was midnight when the Fifty-First Illinois moved out into the river, aboard the D. G. Taylor. The regiment had company—horses and cannon and infantry companies—part of the price the Fifty-First paid for being a small, eight-company regiment. Henry Hall of the Fifty-First wrote, "We have on our boat our own regiment, 3 companies of the Yates Sharpshooters and a battery of artillery"—Captain Charles Houghtaling's eighty men, six artillery pieces, gun carriages, limbers, and horses. The men were a little critical of their cruise ship. Moody said the D. G. Taylor was a "poor boat with very leaky decks" and without anything like half-way decent accommodations.

Even with thirty-plus transports and days of planning, there was not enough room for all the cavalry on board and some horses and horsemen were left on shore waiting for additional steamers to transport them south. Wills of the Seventh Illinois Cavalry wrote, "Word came at nightfall that there were not enough boats for all and the cavalry would have to wait the morrow and more transports. We lay on the river banks that night, and the next day all the cavalry got off except our brigade of two regiments. Another night on the banks without tents... What the devil we are going to do is more than three men like me can guess" (82-3). Wills' regiment never did make the trip downriver to Fort Pillow.

Years later Pope recalled the beginning of the Fort Pillow campaign: "When all was ready Commodore Foote with his gunboats took the lead and the great convoy of steamers followed, each brigade and division being kept together and following in the order assigned them." Lieutenant Colonel Luther Bradley of the Fifty-First wrote home on April 14 from on the river, "Gen. Pope leads the flotilla of transports on the [flagship J. D.] Perry. Next comes our Division which is now the leading division of the army having the right permanently assigned to it. The [D. G.] Taylor & [N. W.] Thomas carry the 1st Brigade and the North Star & Meteor the 2nd." Pope wrote, "It was a grand sight, this great fleet descending the great river and loaded with men and munitions of war. The health of the command was excellent and their spirits bordering on the boisterous. They had been supremely successful and had sustained no loss in achieving great results. They believed themselves capable of anything and longed for the opportunity to show it" (Memoirs, 61-2). The Missouri Republican called the voyage the "pleasure trip to Fort Pillow". At one point in the river journey Bradley wrote to his family, "As I write there are 37 boats in sight coming down in a long line two abreast. The day is one of the blandest and clearest, and the great river is as smooth & shining as glass. The steamers are decked with flags...their decks filled with troops & bands playing. It is a sight worth seeing at any cost." Pittenger wrote in his diary as he sat in his spot on the Old Tub Admiral, "River pretty full."

About fifteen miles below New Madrid the Confederate Mississippi fleet waited, more to threaten, annoy, and observe than to attack the Federal armada as it came down the Mississippi.

By early morning of the 13th, the infantry transports had been underway for fourteen or fifteen hours. The leading transports came up with Foote's gunboats, which had sighted Confederate gunboats down stream. The leading transports landed to wait for the rest of the fleet. William Austin of the Twenty-Second Illinois, on board the "Meteor", wrote, "Our fleet comes gathering in until the shore is lined for miles." The men disembarked, visited friends on other boats and cooked breakfast on shore. The Federal fleet was now within 40 miles of Fort Pillow. The Confederate fleet let its presence be known. Austin wrote, "At 9:30 A.M. our gunboats start out to engage the enemy's boats, who have been sticking their bows around the point to look for us. There goes a gun flash from the Benton's side—the shell bursts far down the river high in the air. A shell from the enemy is seen to explode over our boats, followed by the report of the gun. Several more shots, and the enemy seek safety in flight. While they are playing war below us, the bands on the transports are making the woods ring with music." Foote reported to the Secretary of the Navy: "At 8 a. m. five

rebel gunboats rounded the point below us, when the [Federal] gunboats, the

Benton in advance, immediately got underway and proceeded in pursuit and when within long range opened upon tbe rebels, followed by

the Carondelet and Cincinnati and the other boats. After an exchange of some twenty shots, the rebel boats rapidly steamed down

the river and kept beyond our range till they reached the batteries of

Fort Pillow, a distance of more than 30 miles" (Official Records [Navies] 23, 4).

The steamers loaded and again headed down the Mississippi. It was Sunday. Services were held on the boats. Austin recorded in his diary, "The day is warm and clear, the trees are putting on their coats of green and Summer seems nearer than appears possible in a ride of one hundred and fifty miles." (Austin nearly doubled the distance.)

PICTURES: Contemporary Drawings of the Mississippi Convoy and Fort Pillow

Fort Pillow. Fort Pillow as a strong Confederate fortress on the Mississippi River was less than half a year old in April 1862. It was an expansion of lesser fortifications and was built under the supervision of Montgomery Lynch, a Confederate engineer, with a unit of sappers and miners, a number of Irish laborers, a large body of Tennessee infantry, and the labor of 1200 to 1500 slaves. The fort was located at a sharp bend of the river on the Tennessee side where there were sharp bluffs—the Chickasaw Bluffs—near the river's edge. The bluffs rose 80 feet above the river. The surrounding terrain was thoroughly rugged and forbidding. In December 1861, Engineer Lynch reported to his superiors that he had "fifty-eight 32-pounder guns" (American Civil War Fortifications 3, 17).

| New York Tribune Describes Fort Pillow. The situation of the Mississippi at Pillow is most favourable for defence. The river at Craighead Point makes a very sudden bend, running nearly north and south, and narrowing so remarkably that at the lower end of the works it is not more than half a mile wide, and at their first batteries is about three-quarters of a mile; bringing all boats within easy range of their guns, and rendering their escape almost an impossibility. Below the point there are two large sandbars which render navigation quite difficult. The fort, by which I mean the series of fortifications, is on the first Chickasaw Bluff, is composed of nine different works, extending about half a mile. The bluff is some 80ft. high, very precipitous and rugged, furnishing an excellent location for defence. The works erected at the base of the bluff and on the bank, at some distance from the river, are very well and carefully built for about fifty guns. The country about the fort is exceedingly uneven and rough, and presents the most formidable obstacles to pedestrians everywhere. There are deep ravines, steep ascents, wild gorges, sudden and unexpected declivities on every hand; while in the rear of the fort there is an unbroken line of heavy and carefully-built breastworks, some seven miles in length, to resist any and all attacks by land. These breastworks are far superior, considering their length, to any others which I have seen during the war. Usually they are merely thrown-up embankments of earth; but these are regularly and scientifically made, with broad parapets, heavy escarpments, and counterscarps neatly lined with timber and firmly secured by deeply-driven posts. (Quoted in The Illustrated London News July 12, 1862) |

As Foote embarked on the Fort Pillow expedition, he reported his most recent intelligence regarding Fort Pillow to the Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, "There are, or rather were, on

the 17th March, upward of forty heavy guns mounted at Fort Pillow, and 1,200 negroes working on the batteries still, to strengthen

this stronghold. The guns mounted are heavy rifled, some five or

six 10-inch columbiads, some 8-inch, and remainder 32-pounders.

We may also meet with some opposition at Osceola [on the Arkansas side of the river a few miles above Fort Pillow] in running down

the river, as a battery is said to be planted there." After Foote's gunboats reconnoitered to within a mile of the main fort on April 13, he further informed Welles, "This place has a long line of fortifications, with guns of heavy caliber" (Official Records [Navies] 23, 4-5). Fort Pillow was a dangerous place, and the heavy rains and high bluffs made it a treacherous place. In prolonged rainy weather the mortars tended, with each recoil, to scoot across the platform of the boat, compromising accuracy and firepower. And Foote's heavily clad—and slow and cumbersome—gunboats, Foote feared, could easily become sitting ducks for the big guns on the cliffs above.

Arrival at Fort Pillow. Late on the 13th the expedition came near Fort Pillow. The steamers stopped on the Tennessee side of the river, three miles above the fort, out of the range of Confederate artillery. Commodore Foote wasted no time. His gunboats reconnoitered the fort, following the Confederate boats until Foote's boats were within range of the fort's shore batteries. Pope meanwhile, army-side, sent small bands of scouts out in yawls, which were "quietly rowed down along the bank of the river" as Pope sought for an approach to or behind the fort that would enable him to work in concert with Foote (The New York Times, report dated April 18, edition of April 28, 1862).

In the afternoon of the 14th the steamer transports and the infantry moved from the Tennessee shore across to the Arkansas shore for the additional safety from long-range guns. The infantry waited assignment, marking time in the war. The Fifty-First marched a few hundred yards inland, stacked arms in a field and, as Moody put it, "spent two or three hours luxuriating on Arkansas soil."

Benjamin Smith of the Fifty-First wrote, "We all land for exercise, while the boat is undergoing a thorough cleaning. One of the men belonging to another Co. got hold of a can of cherries. Sitting under the shade of a tree, he proceded to devour them, seeds and all; some of his comrades wanted a taste, but he got away with the whole lot... In two hours he was a dead man; I suppose the cherry stones he swallowed caused his death."

Pope's scouts prodded the river's shores, on both sides. Foote's fleet continued to reconnoiter. William Austin wrote, "Our little tugs, the gunboats orderlies, are skimming over the water, reconnoitering the enemy's position." In the afternoon Foote's mortar boats rained shells onto the Confederate positions, without doing serious harm. On the 15th, the infantry still had no work. General Paine ordered the division to march out to a grove and hold a public service of thanksgiving for the denouement of the New Madrid-Island No. 10 campaign. Men hunted deer and roasted venison. They gambled. Austin wrote, "The day is warm and the shore is lined by bathers." They washed clothes, snuffed out the lives of lice, and fought off mosquitoes. William Gardner of the Fifty-First Illinois remembered Fort Pillow as "the rendezvous of the gnat tribe." Henry Hall thought the Arkansas interlude "a monotonous life... tent life was replete with activity, compared to this—cramped up among nearly 1000 men, cannon, caissons, baggage wagons, artillery horses, and quartermaster's mules, company and commissary stores... We sleep on the floor of the deck and drink muddy Miss. water, which isn't so bad when you get used to it and drink it without looking at it... the color of it is about that of an aged buff envelope."

Intermittently, while the infantry and cavalrymen of Pope's army cleaned the steamers, marched about in Arkansas near the river, and fought mosquitoes, the Federal and Confederate gunners harassed each other. George R. Yost, a sailor on one of Foote's gunboats, wrote, "I frequently saw as many as a dozen shells in the air at one time, crossing each other's fiery tracks; some of them burst in mid air, some landing in the water, others in the heavy woods of the Arkansas shore. One shell, a very large one, passed directly over our upper deck, where I was sitting, missing our wheel house about twenty feet " (Tucker, p. 196). The shell struck the water—a direct watery hit—like most other Confederate strikes. To see the contest between the Federal and Confederate river gunners, men of Pope's infantry had to hike several miles. Campbell of the Fifth Iowa did so, "I went down to the levee this morning to within 300 yards of the mortar boats and witnessed the firing between them and the fort. The sight of the shells as they leaped from the monster mortars and flew through the air was grand, while the roar of the mortars was terrific. The enemy made some close shots in reply to our mortars but happily missed their mark" (pp. 36-7). The Federal gunboats were not much more effective though there were reports that the gunners had found the range of one of the campsites inside Fort Pillow and forced it to relocate. The heavy river fighting was reserved to May and June.

Pope Abandons Fort Pillow. On April 16 the infantry and cavalry cleaned boats and cooked rations—and waited for their part of the Fort Pillow mission to begin. But, it was to be otherwise. At sunset abruptly came the order to be ready to embark in an hour. The men were dumbfounded. Otis Moody of the Fifty-First wrote, "The surprise occasioned by the order was only equaled by the chagrin with which it was received — not that we were unwilling to go where most needed but we had undertaken to open the Mississippi—it had become a sort of pet scheme with us, & we felt disappointed at being compelled to abandon our work." Albert Tilton of the Fifty-First wrote home that the "orders from General Halleck to go to Corinth... did not please us much as we had hoped to follow the river to N. Orleans." Pittenger wrote in his diary, "Late this evening we were ordered up the river... This seems strange." A heavy storm delayed the planned sudden departure until the next day, but Memphis was already receding in the drizzle.

April 17 marked the end of the Arkansas picnic. The rain extinguished the glow of the riverboat idyll. Pope left two Indiana regiments under Colonel Graham Fitch behind to cooperate with the Foote's fleet in reducing Fort Pillow. The rest of his army started steaming back up the Mississippi at daylight on the 17th, "our destination being unknown" (Austin). And so it was for the rank and file. However, Henry Howland, quartermaster of the Fifty-First, was soon in the know and wrote home on the 17th, "We were getting along very finely till last evening we received orders from Gen. Halleck for Gen. Pope to return with his entire army with the exception of the gunboats and mortars and proceed up the Tennessee to aid our troops at Pittsburg"—hence the abrupt order of the evening before, and it was not long before every private had an idea where the convoy was headed. Captain J. Harvey Greene of the Eighth Wisconsin Infantry wrote to his wife on the 19th, "The orders now are, as popularly understood on board, though not definitely known, that we are to go up the Tennessee river to reinforce Grant's army."

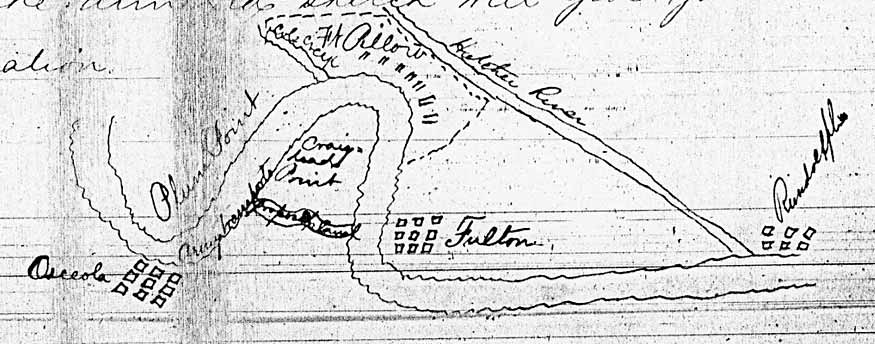

Above: Thomas Scott's April 16, 1862 Map of the Situation at Fort Pillow. The course of the Mississippi is always changing. However, Osceola, Arkansas is always north of Fulton and Randolph, Tennessee. The lines and strip of text cutting across the loop of the river—around Craigshead Point—read, "proposed channel" and offered the chance of a relatively short digging effort to put infantry and cavalry both above and below Fort Pillow.

Abandoning Fort Pillow—Why? The process that aborted the Fort Pillow expedition was set in motion even before Pope's convoy left Island No. 10. Shiloh was fought on April 6 and 7. Both sides had fought their armies to exhaustion. It would take time to recuperate, refit, and supply. However, the Confederacy was already taking steps to reinforce Beauregard at Corinth. Grant wrote to Halleck on April 9:

GENERAL: There is little doubt but that the enemy intend concentrating upon the railroad at and near Corinth all the force possible, leaving many points heretofore guarded entirely without troops. I learn this through Southern papers and from a spy who was in Corinth after the rebel army left.

They have sent steamers up White River to bring down Van Dorn's and Price's commands. They are also bringing forces from the East. Prisoners also confirm this information.

I do not like to suggest, but it appears to me that it would be demoralizing upon our troops here to be forced to retire upon the opposite bank of the river and unsafe to remain on this many weeks without large re-enforcements. The attack on Sunday was made, according to the best evidence I have, by one hundred and sixty-two regiments. Of these many were lost by killed, wounded, and desertion. They are at present very badly crippled, and cannot recover under two or three weeks. Of this matter you may be better able to judge than I am. (Official Records 10/2, 99-100) |

The reports of Confederate reinforcements moving toward Corinth were correct. Van Dorn and Price were on the way, and so were various detachments from other places, east and south—regiment-sized, demibrigade-sized, brigade-sized. Halleck was alert. Federal commanders were not panicked—not fearing that somehow Beauregard would pull his army together and attack on the 11th or 13th—but timetable was for them of the essence. It would take two or three weeks for Beauregard to recover fighting trim and time for the gathering forces to gather in Corinth and augment the Confederate army. But, even considering that, Grant suggested to Halleck that "large re-enforcements" were necessary to secure the Federal position at Pittsburg Landing. The primary candidate for "large re-enforcements" was Pope's Army of the Mississippi. It was currently pursuing a mission, the abandoning of which would not jeopardize Federal lines or positions though it would delay the strategic aggression of Federal forces along the Mississippi and the opening of the Mississippi Valley. It would take the Army of the Mississippi five days to boat the Mississippi, the Ohio, and the Tennessee, from Fort Pillow to Pittsburg Landing. If the time required to take Fort Pillow was short, the Army of the Mississippi could stay and complete the mission with Foote and move on Memphis, broadening the front against Beauregard to the west, forcing Beauregard to thin his line of defense from the Tennessee River to the Mississippi River. If the time required at Fort Pillow was not short, then the Army of Mississippi might be banging away, stymied, at Fort Pillow, leaving the two armies on the Tennessee alone to fight the Confederate assembly at Corinth.

Foote, from the naval side, was of the opinion that the mission would take only six days, four to capture Fort Pillow and two more to get to Memphis. He reported to naval command that he and Pope had "made such arrangements, that by combining our own with the forces of the army, that our

possession of this stronghold seemed to be inevitable in less than six days" (Official Records [Navies] 23, 7-8). If Foote's calculations were true, Pope assented to them, and time were assumed to be the only factor that mattered, then Pope's proper place was Fort Pillow.

The army, however, was laboring under a different set of assumptions and alarms—Pope's apparent unity of opinion with Foote notwithstanding—and was developing its own timetable. Probably on April 13, Pope had news of the Confederate forces moving across Arkansas toward Memphis—and eventually Corinth—to reinforce Beauregard. This raised the prospect of either reinforcements reaching Beauregard before reinforcements reached Grant and Buell—if Van Dorn's army pushed on to Corinth; or, of a big fight for Pillow and Memphis if Van Dorn held his army at Memphis. Time was becoming more of the essence.

Within hours of arriving off Fort Pillow on April 13, Pope had begun exploring the Tennessee shore, looking for a route that would allow infantry to attack the fort from the rear while Foote attacked from the river. Such an approach would allow quick operations with Foote's boats; Pope's army would brush past fallen Pillow and strike Memphis.

But, this was not the right Spring for all that. Most of the Mississippi Valley was flooded with a hundred-year flood. The Tennessee side offered no decent ingress, within a tolerable distance, for infantry operations. Foote reported to Gideon Welles on the 14th, "General Pope has returned with his transports, and informs me that he is unable to reach the rear of the rebels from any point of the river above" (Official Records [Navies] 23, 5).

Opposite Fort Pillow, however, a levee protected the Arkansas side from flood waters. At first therefore Pope thought to cross Craigshead Point by land. In this way he would put forces below Fort Pillow (see Scott's map), cross the Mississippi with infantry forces, and attack Fort Pillow by land from below while Foote bombarded the fort from the river. But that workable plan was soon ruined; Confederates cut the levee on Monday, the 14th; soon the Arkansas shore was also a sea. Pope was confronted with flooded wetlands everywhere.

In the face of that Pope and Foote sketched out two plans. The first was to dig a canal about six miles long across Craigheads Point, "leaving the river 5 miles above Fort Pillow and intersecting 4 miles below about opposite the Village of Fulton," according to Scott's summary for Edwin Stanton (dated April 16th, 9 a.m., On board Steamer J. D. Perry;, Miss. River near Ft. Pillow). This plan entailed cutting a canal through the wooded waters now submerging Craigshead Point (very much like the effort that made Island No. 10 untenable for its Confederate defenders). General Pope, Scott wrote to Stanton, "if he decides upon the plan, will set Bissell's force [First Regiment Missouri Engineers] to work tomorrow [April 17] cutting timber below water far enough to give 6 or 8 feet water...to pass the whole fleet of transports if necessary." The second plan under consideration envisioned making use of an old bayou to the north of Fort Pillow on the Tennessee side. Pope would move his infantry transports up the bayou into the bluffs as far as possible, "land his force and march upon the rear of Fort Pillow—distance of navigation from Miss River to bluffs, about 25 miles—land movement from bluff to fort about 30 miles - requiring about 6 or 7 days to reach the fort with the army."

Thus, there was no route to quick triumph at Fort Pillow. Yet, in the mind of Federal decision-makers, the looming threat from Beauregard grew more threatening—with Confederate reinforcements hurrying to Corinth.

Pope and Scott reached a commonality of purpose and communication. In later years Pope wrote of the six weeks when Scott "made his home" with Pope. Pope said, "I could not have wished nor have had a pleasanter or more acceptable guest. He was a man of wonderful intelligence and quickness of perception, a keen observer and a most energetic and zealous participant in all that went on... He was everywere and saw everything and a more genuine, cheery good humored friend and companion I never met... He came to us unknown and left with the strong friendship of many of us and the regard of all." Scott traveled upriver on a dispatch boat to New Madrid late on the 14th, so he could better receive and send communications for Pope. Scott consistently represented the view that Pillow required too much time. On the 14th, Scott messaged J. C. Kelton, Halleck's assistant adjutant general, "Do you want his [Pope's] army to join General Halleck's on the Tennessee?...Fort Pillow strongly fortified. Enemy will make a decided stand. May require two weeks to turn position and reduce the works" (Official Records 10/2, p. 106).

The crux of the matter was in the phrase "may require two weeks." Pope controlled army communications from Fort Pillow and could slant them toward chosen ends; Pope let Scott be his mouthpiece in manipulating Halleck's decision-making. In Scott's communications the count of days required to accomplish the Pillow-Memphis mission was padded (whereas in Foote's communications the count was shaved.)

On the 15th, Scott wrote to his boss Edwin Stanton, "I arrived here [New Madrid] at 9 o'clock by steamer to give you information and with dispatches for General Halleck. He cannot be reached by telegraph [Halleck had recently arrived at Pittsburg Landing from St. Louis]. If General Pope finds, after careful examination, that he cannot capture Fort Pillow within ten days, had he not better re-enforce General Halleck immediately, and let Commodore Foote continue to blockade below until forces can be returned and the position be turned by General Halleck beating Beauregard and marching upon Memphis from Corinth?" Army opinion—Pope's and Halleck's (Stanton, in this case, gave Halleck free reign)—shifted against the Pillow mission.

Pope grew impatient with the Mississippi, especially since Foote was hesitant shoulder the risk involved in making a direct attack on Pillow's bluff and water batteries, thus increasing the likelihood that an impatient army would be mired in Arkansas swamps wrangling with Foote at each move.

Assistant Secretary Scott wrote to Stanton on April 16, "Commodore Foote is a faithful conscientious officer, brave personally as a man can be, but very cautious in regards to his fleet—fearing injury to boats might render them so helpless that enemy could pass up the river and do great damage." Scott added, "This view of course is entitled to great weight." But clearly Pope, army-side, was less concerned than Foote about the loss of a boat here and there. On the same day, in another Scott-to-Halleck missive, Scott wrote that the "canal project, as opposed to the seven-day bayou-and-overland-march project, would likely be adopted, "provided Commodore Foote can be induced to assume a little risk and pass the fort with about 3 gun boats."

Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Gilbert of the Thirty-Ninth Ohio wrote to his wife on Tuesday, April 15, from onboard his steamer, "Here we are yet—old Foote is afraid to let his gun boats go close enough to fight the batteries of Fort Pillow, so we are still lying above the 1st Chickasaw bluffs. Pope is as mad as man can be at the delay; the rebels are represented as strongly fortified, but we believe a dash at them with gunboats & mortars would cause them to get..." This was an easy opinion for an army man, or an army commander, to cherish—enough to partially inform Pope's preference to move on with his command.

On the 15th Halleck issued the orders for Pope, "Move with your army to this place [Pittsburg Landing], leaving troops enough with Commodore Foote to land and hold Fort Pillow should the enemy's forces withdraw" (Official Records 10/2, 107-8). Halleck also informed Foote by telegram and suggested that Foote continue with the bombardment of Fort Pillow. Pope learned of the order on the 16th and formally notified Foote that he was ordered to Pittsburg Landing: "I move with my command tonight" (Official Records [Navies] 23, 5-6). Thus the first part of the day of April 16 was spent in planning how to take Fort Pillow and the latter part was spent in making army arrangements to abandon it.

But there remains the question of the soundness of the decision to move the Army of the Mississippi post-haste to Pittsburg Landing at the expense of the Fort Pillow mission. The Fort Pillow mission was not, as Foote insisted, a six-day affair, but would a two- or three-week mission have jeopardized the Federal campaign against Corinth?

The decision was based on the view that Confederate strength was growing at a threatening rate, the view (as stated by Grant above) that "large re-enforcements" were needed to secure the armies of Grant and Buell on the left bank of the Tennessee River, and the apprehension that Pope might be stuck at the Fort Pillow just when the Federal effort desperately needed his advance on Corinth from Memphis.

Hindsight says it was not necessary to move the Army of the Mississippi from Pillow to Pittsburg. Naturally Halleck and his sources of information over-estimated (by 100 percent) the forces that were coming toward Memphis and Corinth under Van Dorn and Price.

Interestingly, on April 15, J. C. Kelton, Halleck's assistant adjutant-general, who was still in St. Louis pending Halleck's establishing a headquarters somewhere in Tennessee, passed on Thomas Scott's telegraphed dispatch (quoted above)—enemy will make decided stand...may require two weeks—to Halleck. Kelton told Halleck what Kelton had dispatched in return to Scott, "I answered that you had intimated no change in General Pope's destination, and said I thought you relied on the re-enforcements General Buell could give you" (Official Records 10/2, 107). Kelton was right. The armies of Grant (Thomas) and Buell out-numbered Beauregard's consolidated forces up through the evacuation of Corinth at the end of May. Pope's army, sheerly in terms of numbers, was redundant in the balance of strength against Beauregard. The Army of the Mississippi provided, however, most of the driving energy of the Federal advance on Corinth—the road-building, bridge-building, road-clearing, and skirmishing reconnaissance between the Tennessee River and Corinth.

No doubt if Pope had championed a continued Fort Pillow mission through Scott's communications, there would have been a combined army-navy operation against the fort.

For all the logistical effort, for all the energy expenditure, for all the planning, the expedition to Fort Pillow bore little immediate tactical fruit. Pope's infantry never participated in hostilities; the fighting was between the guns of the fort and Foote's mortarboats. Most of the infantry and cavalry men, except for those engaged in scouting and yawling, never even saw Fort Pillow; they were too far upriver, and the fort was hidden in the bluffs and the water batteries were at the base of the bluffs. They only saw traces of missiles flying through the air and the dark emissions of gunboat stacks and heard the concussion of great artillery guns.

The Fort Pillow mission agitated Beauregard and Bragg in Corinth as they prepared to attack or defend against Halleck.

Their actions give a glimpse of how events would have transpired had Pope pressed the attack against the fort and moved aggressively against Memphis.

As long as Pope and Foote posed immediate threat to Fort Pillow, Beauregard and Bragg hesitated between directing the approaching forces of Van Dorn and Price to Fort Pillow or to Corinth, once those forces arrived in Memphis. Bragg opined to Beauregard that Fort Pillow was a more crucial point than even Corinth, and Beauregard agreed—for the loss of Pillow would bring the loss of Memphis and of the western terminus of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Pope would threaten Corinth from the west while Buell and Thomas threatened from the east. Beauregard prepared to move Van Dorn's army from Memphis to Pillow if Pope pressed the attack against the fort. Van Dorn's army was held at Memphis, rather than hurrying on to Corinth, as long as Pope was on the Mississippi.

Indeed, for a time Beauregard reassigned Corinth units to Fort Pillow. Those units were on the move away from Corinth when Pope headed back upriver, at which time the orders were rescinded.

Taking and holding Fort Pillow and Memphis would have allowed Halleck to work on a broader front, stretching Beauregard's strength even thinner. But Halleck thought he could better ward off any disaster at Corinth by starting with overwhelming strength at the Tennessee River. Hindsight tells us that he over-resourced there and subsequently failed to use his resources fully. When Halleck abandoned Fort Pillow and put all his energy into the war on Corinth at the Tennessee River, Beauregard brought on Van Dorn; he brought all his numbers to Corinth. The Confederate Mississippi fleet and an infantry garrison of five thousand defended Fort Pillow against Foote and his successor.

Back Up the Mississippi. As the Army of the Mississippi steamed away, back up the river, Pittenger recorded, "Heavy cannonading is heard in the direction of Ft. Pillow. Old Commodore is probably trying to get his foot in it." The Old Commodore complained about Pope's abrupt departure for a week and through several pages of the Official Records. The convoy headed upriver on April 17—Pope's Steamboat J. D. Perry far in the lead.

At mid-morning, the fleet caught up to Pope's flag-ship, which was taking on stores from the commissary boat. "The whole fleet," Austin wrote, "comes clustering up like bees for provisions." The upstream going was slow. The rain came down in sheets. Otis Moody of the Fifty-First wrote, "The rain continues to pour in torrents, & it is optional to stand outside & take it clear or retire below and receive it through the numerous cracks & seams, in the decks. There is very little comfort & less enjoyment in prospect for this trip. Officers can get their meals below on the boat such as they are for fifty cents each while the soldiers have two stoves, in the after part of the boat for six or seven hundred men on which to make their coffee. Stopped once during the day to take on wood where the men were obliged to wade waist deep in water to get to it."

The last days on the river were becoming as miserable as the first had been diverting. The Fifty-First Illinois was, in Henry Buck's words "'cooped' in the close, crowded, dingy transport." Houghtaling's wet artillery horses stank up the boat and beshat the decks. Colonel Bissell of the Missouri Engineer Regiment recalled the end of the trip, "It rained almost continually, with nearly a thousand men crowded upon one boat, filling every nook and corner of it. Few could secure shelter, and by far the larger number had to brave the tempest and endure their wet clothing, many sleeping in pools of water...The facilities for cooking were so poor that some could get but one meal a day." Lieutenant Colonel Bradley of the Fifty-First Illinois wrote home, "We had a thousand men on a moderate sized steamer. At night every square foot on each deck was covered with sleeping men... it rained constantly, keeping us wet nearly all the time as the steamer leaked through all the decks and the sides of the western boats afford no protection being as like an eastern steamer as a summer house is like a prison."

Late on the 17th the rain dwindled away for several hours, "giving us," Moody wrote, "a little relief from close confinement & dirty water."

Captain Greene described that first northbound night on the Mississippi to his wife:

| I never looked at a more magnificent sight than presented itself last night just before we rounded to and stopped. We were going round a bend in the river when one by one headlights of steamers became visible below us, increasing in number and rapidity as we cleared the point, until it seemed as if by magic a thousand red and white lights and a thousand bright furnace fires glittered and blazed on the water, making the darkness around us blacker than ever. All at once as if to complete the scene, the bands and drum corps of the whole fleet struck up tattoo, filling the air with a perfect medley of music. Gradually the notes of the bugle could be distinguished, then of other instruments and soon the medley of an entire band would come over the water. Our men... quieted down, scarcely whispering, subdued and fairly entranced by the beautiful sight and the music from the darkness, for the boats themselves were invisible. The lights looked as if suspended on nothing. |

The morning of April 18 found them still churning upstream in intermittent rain. The lead boats of the fleet reached New Madrid—"this home-like point," Pittenger called it—at 2:00 p.m., stopped and took on coal. The boilers of the "Chonteau," carrying the Fifth Iowa Infantry, began to leak as the steamer approached New Madrid; it made poorer and poorer headway against the Misssissipp current. At New Madrid the Chonteau was lashed to the powerful "City of Alton" and the tandem—the Chonteau's engines assisting as they could—continued the journey on up the river towards Island No. 10. The "D. G. Taylor" and the Fifty-First passed the now famous island just before dark (other steamers passed the island long after dark). The steamers on water gave the men a different view than they had had of the Island when they drove Confederate forces off it. Moody wrote, "We reached the island about 5 1/2 & luckily it was one of those intervals of cessation from rain, so that we were able to stand astride & witness this spot, which was for itself such a memorable place in history. Approaching the island from the south there is nothing remarkable in its appearance - the lower end of the Island is heavily wooded & and at this stage of the water nearly submerged. We passed between the island & [Missouri] shore, some of the other boats taking the other side. Toward the upper end of this island the land becomes higher & opens out broader. There are two earth work fortifications on the west side of the island, mounting three or four guns each & a much larger & more formidable one at the head of the island.... Had this fleet attempted to pass this point at that time, it would have been sunk in ten minutes. Now we sail past with as strong a feeling of safety as one would ride in the street cars of Chicago."

The men of the Fifty-First woke up on the morning of the 19th to find their boat tied up in Cairo, Illinois, that city they as well as numerous other regiments had passed through two, three, or four months earlier on their way to their wartime tasks. Some regiments were not allowed to leave their boats in Cairo—some steamers were scheduled to take on coal there and then sail on—but the men of the Fifty-First Illinois managed to get into town, along with many men of other regiments. "Now commences a grand struggle between the men to get on shore & the officers to keep them on the boats," wrote Moody,