Captain William H. Greenwood

Captain William H. GreenwoodCompany H

Captain William H. Greenwood

Captain William H. Greenwood

Company H

Greenwood was born in Dublin, New Hampshire on March 27, 1832. He studied engineering at Norwich University, the Military College of Vermont, graduating in the class of 1852. In late 1852, Greenwood migrated to the West and took up residence in Galva, Henry County, Illinois. His father and step-mother soon followed and settled nearby in Illinois. Prior to the Civil War Greenwood was employed in engineering activities related to the expansion of railroads. Galva itself was a brand new far-western Illinois town, where two new railroads crossed. He first worked as a civil engineer on the line of the Central Military Tract Railroad, which was later known at the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy. He moved on to the American Central Railway and worked there until the outbreak of the Civil War.

In 1857, Greenwood married Evaline Knight of Dummerston, Vermont. Greenwood's railroad undertakings were engineering successes for him, but his own financial investment in those undertakings brought lackluster returns and showed little promise for the future. The army-building response in Illinois to Lincoln's calls for volunteers seemed to offer Greenwood an avenue to both do his "duty", as he often referred to it, and to build toward the future. In 1860, he was a man of both sensitivity and ambition—not overflowing with self-confidence. In late 1861, he wrote to Eva, as he was trying to raise a company of men for the war, "I fear my poor luck has not yet left me and I fear that I shall fail in this the same as I have in all other things."

As it turned out, Greenwood's fears did not materialize; on the contrary: Greenwood's Civil War career challenged and amplified his native abilities and engineering experience and made of Greenwood a self-confident man who filled his remaining years with undertakings.

GREENWOOD'S MILITARY CAREER, THE BEGINNING. When Lincoln issued his first call for 75,000 volunteers, Greenwood offered his services as an engineer to Governor Richard Yates of Illinois. The response to Lincoln's call was overwhelming, and Yates did not need to take up Greenwood's offer. With the next call for volunteers, Greenwood, in early October 1861, began recruiting a company of "sappers and miners", or skilled tradesmen and laborers, for a regiment that Colonel Waters McChesney was recruiting—known in the newspapers and correspondence as the "Rock Island Regiment". Greenwood recruited about 15 to 20 men, but associates of his were supposed to recruit like numbers; together they might build a company. In November, Greenwood and some of his recruits went into camp in Rock Island and started driling; at the same time Greenwood continued his recruiting efforts. A captaincy was at stake; enough recruits would almost assuredly equate to a captaincy, less men to a lieutenancy.

In December McChesney was ordered by the adjutant general to move his "regiment" to Chicago's Camp Douglas, the training camp of Illinois' northern military district. McChesney moved to Camp Douglas with six half companies of men, a total of just over 200 recruits. There were other regiments at Camp Douglas in formative stages, and the governor and adjutant general of Illinois were more interested in full regiments than stub regiments from the various corners of the state. McChesney's regiment was one of the smallest and, in mid-December, it was appended to the Forty-Fifth Illinois, the "Lead Mine" Regiment. However, a number of McChesney's squads of men with their would-be-lieutenant leaders refused, and, instead embarked on a period of frantic brokering and horse-trading to fill out companies in other regiments that were eager to get up to strength. Only two companies of the disintegrating McChesney-Rock Island Regiment joined the Forty-Fifth. There was pressure on Greenwood with his men to become a part of a company of the Forty-Fifth Illinois. He refused. Another possibility presented itself: Greenwood's squad might fill out Captain Nathaniel Petts' Iroquois County company which had just become a constituent of the Fifty-First Illinois. The first lieutenancy of Petts' company was firmly in the hands of Albert Tilton, but the second lieutenancy would fall to the leader of the body of troops that completed the company. It looked promising.

But, then, on Christmas Day, more Rock Island County men, western Illinois men, arrived in Camp Douglas. Port Byron, Illinois minister John Whitson. Whitson had twice—maybe two and one-half times—as many men as Greenwood, but still not enough to constitute a company. Greenwood and his squad were likely worth a first lieutenancy in Whitson's to-be company. The Fifty-First Illinois was still three companies short, so Colonel Cumming was eager for a Rock Island company to come together as part of the regiment. It did. In December, this conglomerate company—Whitson and Greenwood, Whitson's Rock Island County men and Greenwood's Henry, Mercer, multi-county men—became Company H of the Fifty-First Illinois, in camp and in training at Camp Douglas, Chicago. Whitson was named captain. Greenwood was named first lieutenant. The date of Greenwood's formal transfer to the Fifty-First Illinois was December 22, 1861.

GREENWOOD'S MILITARY CAREER, IN THE FIELD. Greenwood served in the field with Company H throughout the regiment's campaigning at New Madrid, Island No. 10, Farmington, and the Siege of Corinth. In late May 1862, however, he submitted his resignation, feeling that Lieutenant Colonel Bradley had cast aspersions on his company, Company H. Bradley, however, did not forward Greenwood's resignation up the chain of command for approval and told Greenwood his, Bradley's, comments were not directed at Company H; on the contrary, Bradley made special compliments regarding Company H. Greenwood withdrew his resignation papers, feeling, he said, responsible for the company, "I considered myself responsible for the company and nearly always had command of it in the field." Indeed, Captain Whitson was ill most of the time, not with the regiment in the field, and died in Chicago in July, 1862.

Colonel Cumming of the Fifty-First had already recommended Greenwood, as an engineer, to General John M. Palmer, who commanded first the division, then the brigade, of which the Fifty-First was a part. On June 19, 1862, shortly after the evacuation of Corinth and before the regiment headed in the direction of Alabama on railroad guard duty, Greenwood was ordered to report to General Rosecrans for duty as a topographical engineer. He was assigned to the staff of General David S. Stanley, who at the time commanded the right wing of the Army of the Mississippi. Greenwood was aide-de-camp to Stanley and topographical engineer. (Greenwood followed Stanley when he became Chief of Cavalry of the Army of the Cumberland.)

When Captain Whitson's vacated captaincy was filled by his younger brother Second Lieutenant Charles Whitson, upon Bradley's recommendation, Greenwood was deeply miffed. To Rosecrans' query as to why a second lieutenant would be promoted over a first lieutenant, Bradley replied that it was thought preferable to have a captain who had been serving with the company rather than one who had been on detached service as a topographical engineer. Greenwood considered it hostility on the part of superior officers. 1863 letter of William Greenwood to Governor Richard Yates of Illinois.

The promotion was important to Greenwood in more than one regard. Military service seemed to offer Greenwood the kind of career advancement he sought. He wrote to his wife on May 5, 1862, "Some of our officers think that we shall be mustered out of service in a few weeks. If we do I think I should try and get up a company of regulars and Join the Regular Army for five years. I like the service and I can do no better anywhere else." When Greenwood pleaded his case with the Governor Yates of Illinois, he wrote in terms of honor and reputation and the personal damage of being passed over for promotion: "I care but little for the extra ten dollars a month, but I do consider it a dishonor to be passed in that way, for it is the natural conclusion for those who do not know what my conduct has been during my term of service to think that it is because I have not done my duty.... My friends know that I received a military education at Norwich Vermont and that I have been successful as an engineer, and wonder why it is that I have not been more successful as an officer, and I dislike to keep telling that it is caused by the ill will of my superior officers, to say nothing of the breach of discipline by so doing" (May 17, 1863, Illinois State Archives).

The younger Whitson was wounded at Stones River on December 31, 1862 and resigned the captaincy on March 18, 1863. Greenwood, unwilling to leave his fate to the bosses of the regiment, appealed directly to the governor of Illinois for promotion to the vacant position. He was formally mustered in as captain of Company H on June 12, 1863; this muster-in was later re-dated to March 19, 1863, the day after Charles Whitson's resignation. Ironically, he never took active command of the company, nor served in the field with it. Greenwood's detached-service topographical engineering and subsequent tasks kept him away at Army of the Cumberland Headquarters. Company command fell to the capable hands of Osman L. Cole. But Greenwood's absentee command did hurt the company: Cole was shot in the face and captured on the second day at Chickamauga as the company and the regiment tried to hang on to a piece of hillside; Cole never returned to the regiment, spending most of the rest of the war in Confederate prison. When the regiment went on veteran—and recruiting and reorganization—furlough in February 1864, there was no one to mind the Company H shop, and the company had no officers on recruiting service; hence, whereas Company G gained 29 recruits during the February-April, 1864 period, Company H gained none. In this regard, Bradley was correct—it was better to have an officer who was with the company than one who was not, though there were plenteous examples, even right in the Fifty-First, of absentee officers being promoted—while they were on disability furlough or confined in prison-of-war camps.

On August 25, 1864, Greenwood was appointed Assistant Inspector General of the Fourth Army Corps of the Army of the Cumberland. Though he continued to hold the captaincy of Company H, this new appointment gave Greenwood the rank and pay of a lieutenant colonel. Poirier's book on Norwich University alumni says that Greenwood was cited for gallantry at Franklin and Nashville (November 30 to December 16, 1864). Shortly after Greenwood's death General David Stanley, who was head of the Fourth Army Corps and whom Greenwood assisted as aide-de-camp, wrote to Greenwood's widow Eva, "I fully understood his worth at the Battle of Franklin. His vigilance averted a disaster. He was sent to observe the enemy's cavalry at Hughes Mills* five miles above Franklin and found Forrest's forces crossing almost unopposed. Quickly rallying cavalry and calling for infantry supports, your husband conducted Genl Hatch to the point and Forrests's forces were driven back across the stream. Had they succeeded in getting a hold on our north side, our trains were at their mercy."

Greenwood continued as assistant inspector general until the Fourth Army Corps was broken up in August, 1865. At that time the Fifty-First Illinois in Texas was whiling away its last month. Greenwood was appointed Assistant Inspector General of the Department of Louisiana and Texas, headquartered in New Orleans.

By stipulation of the War Department dated July 9, 1865, Federal officers who were due to be mustered out were allowed to remain in the South and be mustered out there without having to travel north for official muster-out. "Commissioned men and enlisted men about to be mustered out of the service with their respective companies or regiments, and who desire, in good faith, to remain in this part of the country, and be discharged at points where their commands are mustered out, will be mustered out and discharged at such points" (from General Order 19, Department of Lousiana and Texas, July 31, 1865). Greenwood made official request to department headquarters on September 15, 1865, saying that he wished to remain in Texas and make it his residence. Greenwood did continue on in Texas and in the army after his old regiment had departed for Illinois and discharge. In October 1865 he was adjutant general of the District of Central Texas. He was not mustered out on September 17, 1865 as some readings of his service records indicate. Mansfield, below, writes that "while still in the service of the government, he rebuilt the Gulf and San Antonio railroad."

GREENWOOD'S RAILROADS. Thus commenced for Greenwood fifteen years of ceaseless, energetic work in surveying, planning, and building railroads from the Midwest into the West. The three biographical sketches linked from this page go into some detail relative to Greenwood's railroad-building activities. The accomplishments from all those years that Greenwood and his colleagues esteemed most highly were Greenwood's being first to propose narrow-guage (three-foot) railroads and the rate at which the Kansas Pacific Railroad, of which Greenwood was the chief engineer, was built—150 miles in 100 days—and over ten miles of track in ten hours on the last day.

SHORT-LIVED DAUGHTER. Greenwood and his wife Eva had no children of their own, but they adopted a daughter who by all accounts was the shining apple of their eyes until death snatched her (still in her childhood).

GREENWOOD'S EARLY DEATH. In August 1880, during Greenwood's planning and surveying for the building of a Mexican national railroad, he was robbed and murdered. The description of those events, reproduced here, is from Mansfield's History of Dummerston (which took the account from a reunion of a Society of the Army of the Cumberland, which took the account from a Vermont newspaper).

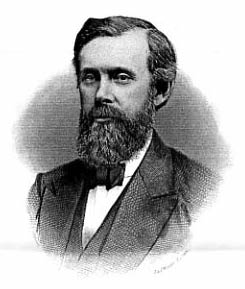

Greenwood

In Later Years

He was murdered near Rio Hondo 18 miles from the city of Mexico, Aug. 29, 1880. He was on his way from Hondo to the city of Mexico, accompanied by Mr. Miller, an assistant engineer, and a servant, where, as was his custom, he expected to spend the Sabbath with his family. When within some 9 miles of the city, he stopped at a wayside inn for the purpose of taking refreshments. Here there were a number of men, who l, seeing his horse, laid a plot by which they were to obtain possession of it. They accordingly rode ahead some distance, where they remained ambushed. Col. Greenwood upon arriving at a barranca, or ravine, separated from his companions and proceeded ahead of them at an increased pace, with the object of examining the locality. His companions saw him as he came from the barranca and descended upon the opposite side of the hill. They hastened in a gallop to join him, when, in a short time, they came upon his dead body lying in the road, perforated by two bullets, one through the breast and left hand, another through the right hand. A letter from P. H. Morgan, dated United States Legation, Mexico, Nov. 23, 1880, to Gen. D. S. Stanley, states that when Col. Greenwood approached where the robbers were in ambush, they rushed out upon him, hoping that the frightened horse would throw his rider, and in that way they might obtain possession of him, and, as in this, they failed, they to make sure of the horse murdered Col. Greenwood. His horse, carbine, and revolver were taken, but his watch, papers, and money were untouched. It is believed that the assassins were disturbed and only had time to make off with the articles mentioned. His body was brought to the capital and buried in the American Cemetery Sept. 1, 1880. The unfortunate occurrence created a sensation in the capital and the loss of Col. Greenwood was deeply felt. The funeral procession was attended by the whole of the Americans and Englishmen, Germans and Frenchmen and many of the representative Mexicans. Over 60 coaches formed the funeral cortege, and 150 persons followed in the sad procession.

In 1882, Greenwood's remains were reinterred to the cemetery in Dummerston, Vermont.

MORE INFORMATION ON GREENWOOD. General David S. Stanley, to whom Greenwood reported for much of his war career, wrote this biography of Greenwood. There are two other biographical sketches on the pages of this site. The three of them share a considerable amount of redundancy, even to the point of exact phrasing, but each provides some fresh information. The sketch in Bernis' History of the Town of Marlborough was written shortly before Greenwood's death. The sketch in Mansfield's History of the Town of Dummerston adduces the most genealogical facts about Greenwood and produces the fullest account his death. If you read only one, read the sketch by David Stanley.

Sources and Notes: