Overviews

Splendid Courage...and Inaccuracies: A Summary of Two Days at Chickamauga

"The splendid courage of the first day is eclipsed by the inaccuracies of the second."

—William Gardner, Company D, Fifty-First Illinois Infantry

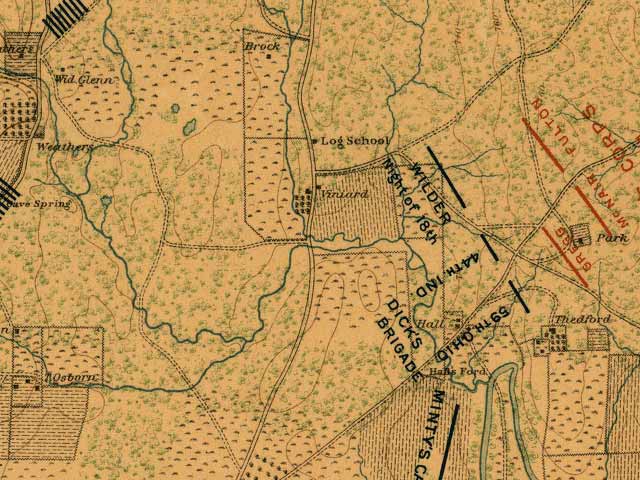

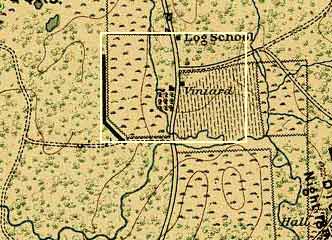

Overview: The Viniard Fields

On the afternoon of September 19, 1863, the Viniard Farm was at the far left of the Confederate line and the far right of the

Federal line. The Lafayette Road ran north and south through the Viniard Farm. The part of the

Viniard Farm under cultivation to the west of the Lafayette Road has come to be known as the "west Viniard field", the

part to the east of the road as the "east Viniard field". Roughly parallel, at its northern reaches, to the Lafayette

Road and 75 yards to the west of it ran what soldiers and reports often referred to as "the ditch". The ditch

angled toward the Lafayette Road and intersected it at the southern boundary of the cultivated Viniard land (west of the road).

The ditch formed a minor shallow valley through the Viniard Farm, with the lowest-lying part of the valley at the southern

reaches of the two fields where the Glenn-Viniard Road debouched on to the Lafayette Road. Lt. Col. William Young of the Twenty-Sixth Ohio described the west Viniard field and the ditch. From the Lafayette Road, he wrote, the field "descends with an easy slope... to a narrow ditch or gully and then rises with a slight grade to the timber in its rear (Wilder's position). The gully varies in depth from 1 1/2 to 3 1/2 feet and in width from 3 to 6 or 8 feet, its border at intervals being slightly fringed with weeds and willows" (OR 30/1, p 669). The ground rose gradually from the ditch to the west and to the east—westward, to the woods bounding the west Viniard field. Eastward, the

ground rose from the ditch to the road; and kept rising—with a very gentle incline—beyond it for 75 to 100 yards and there crested—or flattened out. The ground then dropped off to the east. Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Raymond's after-action report (Fifty-First Illinois) referred to the

"crest of the rising ground". Colonel Johathan Miles' after-action report (Twenty-Seventh Illinois) referred to it as "the eminence" and "the crest

of the eminence". The eminence was (is) slightly off kilter vis-a-vis north-south and vis-a-vis the Lafayette Road; the crest of the rising ground angled from northeast to southwest, across the field, 25 yards further east at the north boundary of the east Viniard field. You can see all this in the period map and the contemporary aerial view immediately below.

|

|

|

Map, Upper Left: The Viniard Place, the Buildings, the Orchard, the Two fields, the Lafayette Road, the "Ditch". In this map snippet (fully cited below) the name "Viniard" is written across the east Viniard field. To the left of the letter "V", the Lafayette Road runs north-south through the Viniard Farm. Across the road from the letter "V" lies the Viniard farmhouse with its grove of trees to the south. The blue-green line running left of the trees marks the course of "the ditch" through the west Viniard field. Sky View, Upper Right: Shows an aerial view of the portion of the map (upper left) bounded by the cream-colored bounding box. This enlarged aerial view (click) shows the 1863 boundaries, the ditch, the two fields, and the crest of the rising ground. |

| Greensward, Above: Taken from the second letter "i" in "Viniard" in the map upper left. Standing at the picture's foreground, you have almost reached the crest of the rising ground. The picture looks northeast toward the woods on the left, from which the "murderous and enfilading fire" came. From the crest of the rise the ground drops off to the east, though green grass against green grass in the photo rather obscures the descent of the ground. | |

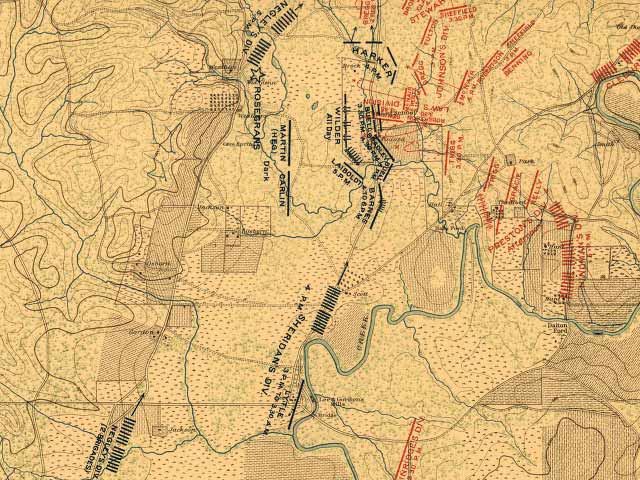

Overview: The Struggle for the Viniard Fields and the Lafayette Road

The fighting on the 19th started on the Confederate right, at the northern reaches of the two armies. The fighting rolled south along the lines. The Confederate brigades attacked east to west, from Chickamauga Creek,

toward the Lafayette Road. Confederate forces tried to shatter the right of the Federal line, so as to be able to attack at the

same time from front and flank—or even to get in the rear of the Federal army. The Confederate left shifted further and further left, south, feeling for the terminus of the Federal right. In the early and middle afternoon, the Federal brigades (Heg's, Carlin's) attacked east across the Lafayette Road, Carlin's brigade at times as far east as the woods east of the east Viniard field. But, the momentum on the south end of the line, around the Viniard Farm, shifted from the Federal right to the Confederate left, the brigades first of Robertson and Gregg, then Trigg, then Benning committed to shooting the Federal right to pieces. Federal command responded by moving two of Wood's brigades (Harker's, Buell's) and one of Van Cleve's (Barnes') into the struggle on the right. Confederate forces pushed these brigades back, inflicting heavy casualties, taking heavy casualties, but hurting some Federal regiments so badly that they had to pull back and regroup, and thus momentum and advantage—despite repeated Federal counter-attacks—fell increasingly to the Confederates as the afternoon wore on toward evening. Chaplain John Hight of the Fifty-Eighth Indiana summed up the first essay of Buell's Brigade to secure the Lafayette Road, at its intersection with the Viniard-Alexander Road near the Viniard farmstead, and drive beyond it—not for the sake of the ground itself but for the integrity of the right wing: "The regiment pressed forward as best they could. But the line could not be maintained, on account of the house, the fence, the stable, and the endless confusion of the hour" (History of the Fifty-eighth Regiment of Indiana Volunteer Infantry, 1894, p. 181).

More than once, in the mid- to late-afternoon, Confederates pushed through the east Viniard Field and the log-schoolhouse woods to the Lafayette Road and as far as the "ditch", which seemed to offer refuge as a staging line for advance across the rest of the west Viniard field, through the woods, and to the Federal rear. But, the tables turned. Here, west of the Lafayette Road, they were stopped by rallied remnants of various regiments, the brigade of John Wilder, armed partially with repeating Spencer rifles, which was arrayed in the woods along the western edge of the west Viniard field—and by Federal batteries. On the occasion of each Confederate advance to the ditch the Federal response was so fierce that Confederate soldiers who were fortunate enough to be alive and ambulatory abandoned the ditch, crossed back across the seventy-five yards to the woods and groves, buildings and fences of the Viniard Farm, or to the Lafayette Road, or to the woods northeast of the intersection of the Lafayette and Viniard-Alexander Roads. And so, the slaughter was mutual, with deaths and wounds plenty.

While Heg, Carlin, Buell, and Barnes' brigades were fighting for their lives around Viniard's Farm, Bradley's Brigade and Bernard Laiboldt's Brigade of Sheridan's Division were hurrying north from Crawfish Springs, just as these other brigades had earlier in the day, at quick time and double-quick time—to be thrown, brigade by brigade into the battle, so as to be and hold the Federal right. Bradley and Laiboldt's brigade were last in line to head north to staunch the flow of Confederate progress in the Viniard fields and keep Confederate forces off the right flank. In the upshot, Laiboldt's Brigade was never called into the fighting on the 19th; Bradley's was. It formed in the woods at the western edge of the west Viniard field. The men of the 51st and the other regiments moved forward, across the west Viniard field, across the ditch, up the incline that carried them across the Lafayette Road, into the east Viniard field, and to the crest of the rising ground. The brigade made common cause in the east Viniard field with rallied men of Carlin and Buell's Brigades. Batteries supported the advance from the rear. This force held in the east Viniard field and along the Lafayette Road. The Fifty-First Illinois and the rest of Bradley's Brigade overnighted there. This is some of the story of that begins to be told on this long page.

Overview: An Old Synopsis from the Chickamauga Battlefield Park

Overview: A Newspaper Summary

The article is by Joseph W. Miller, the correspondent of The Cincinnati Commercial. The facts are straight save that it was not Wood's two brigades but rather one of Wood's and one of Davis' and scattered groups of other brigades that rallied behind Bradley—and also on the flanks and even at points to the front.

September 19 — I glance at the sun, and my very heart sinks to see it still an hour and a half high. The left had already absorbed the centre, and the centre and right had already absorbed every brigade in the army, except one holding a vital point. I followed Sheridan’s swift brigade. I soon saw the right of our line, in confusion, falling back rapidly under an appalling fire. Sheridan’s 3d brigade—the 22d, 27th, 42d and 51st Illinois regiments—commanded by that true gentleman and soldier, Colonel Bradley, deployed into line, and the very instant its flanks turned to the front, it pushed into an open field at a double-quick, while behind it Wood’s two brigades rallied and gathered up their scattered groups. I heard a cheer, loud and ringing, and riding up behind the line of Colonel Bradley’s charge, I saw four noble regiments far across the field, pouring swift volleys into the flying foe, and flapping their colors in triumph. Their cheers subside, and a sharp shower of balls warned me away from the inspiriting sight. In a moment Sheridan dashed back to the rear, halted, but his eyes aglow with pride for the brilliant charge of his brigade. His practical ear had caught the warning musketry rattle of a counter charge, and he threw his second brigade into line for another charge, if the other one is compelled to give way. But it did not give way. Inspired by Sheridan and Bradley it withstands the shock and its assailants hastily retire.

[J. Cutler Andrews, The North Reports the Civil War: "Few newspapers were as widely read in the western armies as was the Commercial; it was frequently called the 'soldier's paper'", (p. 28). Albert Tilton of the Fifty-First wrote home shortly after the Battle of Chickamauga, "I sent father 2 papers with the accounts of the Cin. Commercial & Gazette Correspondents. That of the Gazette is a garbled, doleful and in many instances a false account written in Cin. after a flying trip, in retreat, from the battle field. That of the Commercial was written in Chattanooga by a former officer of the 21st Corps, a brave man, an actual Eyewitness, competent to judge in military matters & withal as you see by his style a talented writer." The onetime soldier now correspondent, Captain Joseph W. Miller, had been an Ohio soldier in an Ohio company mustered in as Company D of the Second Kentucky Infantry. Miller enlisted in June 1861; he mustered in as first lieutenant and was promoted to captain when the captain of his company was killed at the Battle of Mill Springs in January, 1862. Miller's career as a company officer ended due to a severe bout of scarlet fever. At Chickamauga Miller was attached to the staff of Brigadier General William Lytle, and he was functioning as correspondent for The Cincinnati Commercial. Miller was on the battlefield until Thomas pulled back to Chattanooga. His obituary stated, "He was said to have written the first correct story of the Battle of Chickamauga," and a comparison of the early reports of the major newspapers bears that out.]

Overview: General Thomas Wood's Summaries

General Thomas J. Wood, supporting Luther Bradley's promotion to brigadier general in late 1863, wrote to Lincoln: "During the afternoon of Saturday the 19th Sept, it was my good fortune to be supported by Col. Luther P. Bradley, 51st Ills, commanding a brigade in Sheridan's Division. I can bear testimony and do it with great pleasure to the very handsome manner in which Col. Bradley brought his command into action and to the good service it rendered. At the moment Col. Bradley's brigade came into action a very heavy and determined attack was being made, which the brigade very materially aided in repulsing."2 Wood drew the text of his recommendation from his after-action report, dated September 29, 1863, in which he wrote, "...the enemy emerged from the woods on the eastern side of the corn-field, and commenced to cross it. He was formed in two lines, and advanced firing. The appearance of his force was large. Fortunately re-enforcements were at hand. A compact brigade of Sheridan's division, not hitherto engaged, was at the moment crossing the field in the rear of the position then occupied by Buell's brigade and the portion of Carlin's. This fresh brigade advanced handsomely into action, and joining its fire to that of the other troops, most materially aided in repelling a most dangerous attack. But this was not done until considerable loss had been inflicted on us" (Official Records 30/1, p. 633).

Overview: Reports in the Official Records

Lt. Col. Raymond's After-Action Report, Fifty-First Illinois

Colonel Nathan Walworth of the Forty-Second Illinois took command of Bradley's Brigade (Third Brigade, Third Division, Twentieth Army Corps) after Bradley was wounded. Walworth's After-Action Report gives a broader context to Raymond's regimental report. Besides Raymond's report for the Fifty-First, the only other after-action report for Bradley's Brigade is that of the Twenty-Seventh written by Colonel Jonathan Miles. Miles' report for the Twenty-Seventh Illinois records the wonder of supping at 6:00 p.m. on the evening of the 20th.

|

Overview: H. V. Boynton's Summary Battlefield Geography The field of the approaching two days' battle is easily defined. The Chickamauga River bounded it on the east, and Missionary Ridge on the west, while that part of the Lafayette or State Road running north from Lee & Gordon's Mills through the centre of the field to Rossville, formed the axis and the prize of the fight. Whichever army secured that, could grasp Chattanooga. It is eight miles from Lee & Gordon's to Rossville. The country between the Chickamauga and the Lafayette Road was for the most part heavily wooded, with much underbrush. It rises gradually and rolls gently from the river back to the spurs of Missionary Ridge. West of the Lafayette Road there are a number of farms, but each of these contained considerable forest, so that only small areas of the field were visible from any point. (H. V. Boynton, "The Chickamauga Campaign," in Campaigns in Kentucky and Tennessee Including the Battle of Chickamauga, 1862-1864. Papers of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, Volume VII. Boston: The Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, 1908: 321-372, p. 344) Federal antagonists faced, generally, east with Missionary Ridge at their backs. Confederate antagonists faced, generally, west with the Chickamauga at their backs. |

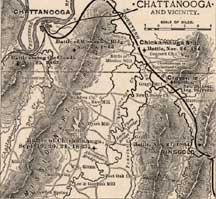

Overview: Maps of Viniard Farm (and the Whole Battlefield)

The maps below are from the map collections of the Library of Congress. There are a number of others. They are all viewable online (search from the Library of Congress American Memory Military Battles and Campaigns page for Chickamauga maps). Mouse-click the little maps below to see a big map.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Top

The Fifty-First Illinois in the Afternoon of September 19

Toward Viniard Farm

The Confederate and Federal armies were collecting toward their collision in north Georgia, had been collecting toward that collision for weeks. The ether was full of their futures. William Putney wrote, "The long, dusty roads, the dreamy, hazy September days...there seemed some sad, gloomy spirit pervading the atmosphere, some impending horror which weighed down and made me feel that something terrible was going to happen, not to myself, but the whole country. Again I can hear in memory's camp the amateur fifer practicing... the calls of the bugle sound again...then they all seemed filled with sadness and melancholy" (National Tribune, September 24, 1885). Indeed. The regimental "Historical Memoranda" trace the regiment's movements from the 18th to the 19th of September: "On the 18th left McElmore's Cove & camped near the scene of yesterday's skirmish just at nightfall. But we were not allowed to stay there long for about 8 P.M. the division received orders to close up on the line of Thomas who was himself closing to the left. Marched that night till 12. On the 19th the division marched on again & manouvered without being engaged till late in the afternoon, listening to the sound of the heavy fighting on our left" (Illinois State Archives, Springfield, Illinois).

On the 19th Sheridan's Division—the three brigades of William Lytle, Bernard Laiboldt, and Luther Bradley—and the Fifty-First Illinois marched on again to Crawfish Springs (Rosecrans' headquarters on the 18th and for a short time—until taken by Confederate cavalry on the 20th—the site of division hospitals of the Federal Twentieth, Twenty-First and Fourteenth Corps). Crawfish Springs lay about four miles to the southwest of Rosecrans' headquarters at the Widow Glenn's on the 19th. Bradley's Brigade arrived there at noon after an eight-mile march. Sheridan reported that his division came into line of battle near the Springs upon arriving there. That point was then the far right of the Federal line, but the line was shifting left, north, as fast as it could be formed. Sheridan added, "Immediately after forming my line, I was ordered to hold the ford at Gordon's Mills with my whole division, the troops on my left having moved to the left, and again isolating me."

Away the three brigades rushed to Lee and Gordon's Mills—as the Federal right was foreshortened—where the road to Lafayette crossed Chickamauga Creek. They formed line of battle and skirmished with Confederate skirmishers who were eyeing the ford there. But, Bradley and Laiboldt were once more ordered left; they moved off northward again; Lytle stayed behind to hold the ford and block the backdoor to the Federal right flank. The right of the Federal right was already left of the army's hospitals—Rosecrans' army had shifted that far left of positions originally envisioned. Sheridan's Division, like those of Johnson, Davis, and Wood, was caught in the scramble to the left as Rosecrans scooted his line north to counter Bragg. In time, that scurry became a by-worded event of the war. George Yuncker of the Fifty-First referred to it as "the memorable move of line to the left" (National Tribune, August 30, 1883). L. W. Day called it "the side-step toward the north" (p. 156).

Until early afternoon on the 19th, though shifting left, all of Sheridan's brigades were in reserve at the south end of the Federal line, first at Crawfish Springs and then at Lee and Gordon's Mills. As Yuncker noted, Bradley's Brigade was the rear-guard of that memorable move; and, it looked as if the division might remain unengaged, on guard duty, south of the fighting. Bradley recalled a moment in the pre-fight hours of September 19:

At the battle of Chickamauga my command was in reserve for a short time. I was changing position in the afternoon and was watching the brigade coming into line, when I noticed the Twenty-Second Illinois on the right with broken ranks and in great confusion. I rode down there and said to the Colonel, "What's the matter here?" Col. Swanwick answered, "Yellow jackets, sir, we've got into a yellow jackets' nest." I said, "Damn the yellow jackets. Get your men into line, we may move any minute." But, we couldn't get them into line. They were hopping about like a lot of lunatics, swinging their hats and slapping their legs, without regard to orders or anything else. We had to form four companies some rods to the rear before they would stand quiet. An hour later we went into the battle, and this same regiment lost 95 men in thirty minutes without flinching.9

At 1:45 p.m., from headquarters at the Widow Glenn's, Rosecrans ordered Major General Alexander McD. McCook, commanding (after a fashion) the Twentieth Army Corps, to move Sheridan from reserve duties on the far right "this way"—i.e. left towards Rosecrans' headquarters. An hour later, at about the same time Buell's Brigade (Wood's Division, Crittenden's Corps) was forming for battle on the Lafayette Road at the Viniard Farm, Rosecrans sent further orders to McCook: "The tide of battle sweeps to the right. The general commanding thinks you can now move the two brigades of Sheridan's up to this place" (OR 30/1, p. 67).

The regiment resumed its march. Couriers raced back and forth between headquarters staff and Bradley and Sheridan, in order to bring the brigade into the fighting quickly and at the optimal place. The march took a zigzag course that reflected the shifting fortunes of the right wing and Federal command's attempt to hold it. Sylvanus Atwater wrote, "Three different times our brigade took a position on the right of the road, to await the approach of the enemy" (Aledo Weekly Record, October 13, 1863). The brigade fronted thrice to the right, to wait for the teamsters to hurry the corps' wagons along within the zone of safety and for the eventuality of the Confederate left pushing around Barnes on the extreme Federal right south of Viniard's; hence L. W. Day's lyric, "[Sheridan] came with rapid strides up the main road, helped Barnes upon his feet as he passed, fell like a withering curse upon Robertson... (Story of the One Hundred and First Ohio Infantry, p. 165).

Colonel Jonathan Miles of the Twenty-Seventh Illinois reported, "...then marched a mile to the top of a wooded hill, where we halted and lay in line of battle a half hour, when we again moved, and in an easterly direction, at a double-quick, about 1 mile to an open field, where we were placed in position, in which, however, we remained but a few minutes, when we were again put in motion, and marched 1 mile in a northerly direction (during the last half mile wounded men were continually passing us to the rear), which brought us in close proximity to the fierce battle then raging." Allen Gray of Company K, Fifty-First Illinois, commissary sergeant at the time of Chickamauga, wrote in his diary of the regiment's penultimate move, "We double quicked over a mile by the road to the Widow Glenn's house - then by the right flank through the woods..." Right flank through the woods—down the slopes of the Glenn hill, marching south, through heavy but not impossible woods—guided more by awful sound than sight (Abraham Lincoln Historical Library, Springfield, Illinois).

Edward Burns of Company K of the Fifty-First, an hour from his death-wound, gave his private's view of the rush to fight, "March in the dust and smoke as both sides of the road was on fire... nearly choked us ...order came and double quick 3 miles and made a charge on the rebs." Sylvanus Atwater, Twenty-Seventh Illinois, wrote, "...such dust as I never saw... the doublequick was enveloped in a cloud as dark as night" (Aledo Weekly Record, October 13, 1863). Edward Crippin wrote in his diary, "Clouds of dust almost choke us as we hurry to the front amid the confusion of booming rattling musketry & orderlies flying in every direction" (p. 281). It was a black and red, ghoulish afternoon of war-eclipsed light, of smoke and fire, burning air and hurtling danger that Federal and Confederate soldiers prepared for each other and themselves.

An Old Fight. In his "Reminiscences" Bradley wrote, "My brigade was ordered into action at Chickamauga about four o-clock on the afternoon of the first day. The rebels had turned our right and captured Estep's battery. So, it was an old fight and a pretty hot one. Sheridan ordered me to drive back two brigades—Trigg's and Robertson's of Longstreet's Corps, which had made the trouble on our right, and re-capture Estep's battery.... We had a monkey and a parrot time of it" (Luther Bradley Papers, United States Army Military History Institute, Carlisle, Pennsylvania).

Indeed it was an "old fight". Confederate forces had crossed the Chickamauga on the morning of the 19th and throughout the morning were aligning divisions and brigades for battle. The brigades of Trigg, Robertson, and Gregg were lined up from south to north opposing the Federal right—or, what was becoming the Federal right. Still as of noon, John Wilder's Brigade was the only Federal presence at the Viniard Farm. At noon, Viniard's was still a farm and still the home of Tabler and Ann Viniard and their eight children. The Viniard Farm had only been the "Viniard" Farm for six or eight or ten weeks—long enough to enter into Civil War lore. Before that the Viniards lived several miles to the west and before that, for most of their years, in Tennessee where Mr. and Mrs. Viniard were born. Viniard's was an ambitious farm, with a double-log farmhouse, with stables, with an orchard to the south and a grove of trees to the north, fences around the yards, farm buildings and a washhouse across the road. A dooryard adjoined that to the east, and it had its own small dense grove of trees.

Wilder's Brigade, on horse and foot, had crossed the fields a time or two and there had been the sounds of battling the evening before, and soldiers had been moving along the road, and the air was sizzling with hostile intentions and there was fire to the north. Toward noon Wilder's skirmish line, over half a mile east of his position in the woods at the western boundary of the west Viniard field, skirmished with the skirmishers of Trigg's Brigade at the southeast corner of the Viniard's east field. Around 2:00 p.m. the war came to sit atop the Viniard Farm: Hans Heg and William Carlin's brigades of Jefferson C. Davis' division advanced east across the Lafayette Road, Heg on the left through the woods just north of the Viniard Farm, Carlin on Heg's right with Carlin's left advancing through the woods and his right through the east Viniard field. They ran into the pickets of Gregg's Confederate brigade. Heg was soon embroiled in war in the woods. Two of Carlin's regiments advanced 700 yards across the east Viniard field (soon becoming trampled corn stalks) and into the woods that lay beyond the eastern boundary of the east Viniard field. There they were countered by the brigade of Jerome Robertson.

At 3:00 p.m. or shortly before, Confederates forces mounted a counter attack and Gregg's, Robertson's, and Trigg's brigades began driving Heg back through the woods and Carlin back through the east Viniard field, back toward the Lafayette Road. Sidney Barnes' Federal brigade entered the battle at the Viniard field. He approached obliquely from the southwest, with a view to hitting the Confederate left flank, and came to the fight where Carlin's regiments were engaged—and utterly without coordination, for his brigade interposed itself between the right of Carlin's line and Carlin's enemies such that the right of Carlin's line was rendered useless. Amidst this tangle of Federal regimental lines, the attacking momentum of Robertson and Trigg struck Carlin and Barnes.

|

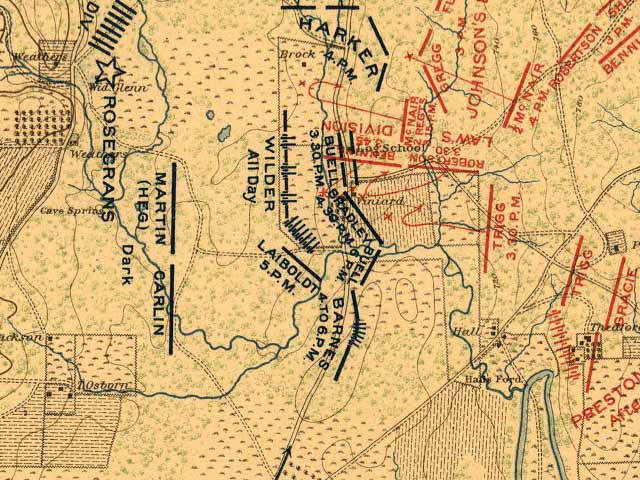

As the Confederate attack pushed westward toward the Lafayette Road, both north and south of the Viniard house, two brigades of Thomas J. Wood's Division, arrived at the Viniard Farm from Lee and Gordon's mills to the south: Charles Harker's Brigade intended at first to replace Heg's Brigade, rushed further north to staunch the flow of Confederates across the road at that point (a mission that dematerialized without demanding Harker). The second of Wood's Brigades, that of George P. Buell, formed its two lines at the intersection of the Lafayette and Viniard-Alexander roads, the first line east of the Lafayette Road, the second west of the road. The location of the brigade line was roughly the same as that of Carlin's Brigade formation an hour before, the left regiment facing into the woods, the right regiment facing into the east Viniard field. Just as Buell's Brigade initiated its advance, Carlin's Brigade was pushed back to the road on top of it—and Carlin's men, after an hour struggle—now becoming a losing battle—intent on crossing back across the road and down below the rise of the rising ground, ran over and through Buell's lines. Panic and chaos spread and much of Buell's force was carried back across the road and down to the ditch with Carlin's, thus a whole fresh brigade of reinforcements was rendered ineffective for the time being—except that their abortive charges inflicted casualties on the Confederate forces, thus weakening them, while at the same time being weakened themselves by their own horrendous casualties. To the north, Heg's Brigade was finally driven back across the Lafayette Road. Confederate forces, lately strengthened by Benning's Brigade having joined the attack, crossed the road and into the west Viniard field. Their objective was to push through the west field, overrun Wilder's men and the several batteries of artillery, and gain the Federal right. But, Benning (like Robertson before him) had pushed too far into the Federal defensive strength. Wilder's men in the woods and behind the barricades at the western boundary of the field—and the men of other commands taking shelter there—pinned Benning's men down in the ditch. Artillery guns enfiladed the ditch, making the shelter a death trap. Benning's men gave up and fled east, back to the (relative) safety of the Viniard trees, the woods across the road in the vicinity of the log school house, and the backside, the downside, of the rise in the east Viniard field. Benning was pushed back, but the Federal right was slipping; each Confederate attack loosened its grip. Confederate forces had gained a thousand yards on it, and they were preparing yet another attack. By the time Bradley was brought into battle enemies had pushed the front from a line east of the east Viniard field back west to the Lafayette Road, which by 4:00 p.m was more Confederate than Federal. Bradley came into line 300 yards to the west of the road, in the woods bordering the west side of the west Viniard field, whereas Buell ninety minutes earlier had formed on the Lafayette Road. There was considerable confusion in the movement of brigades on the Federal right all afternoon. Bradley's Brigade was committed to the fight in a fairly premeditated way, and with an understanding of the Confederate threat and the disarray of the Federal right. One might say that this last initiative on the Federal right was the first and only one that was semi-well-coordinated, the understandings on which it was based not already obsolete before it began. |

|

Wood's Advance: "Our Little Line".

(We discuss Wood's advance so as to understand the time and place and ongoing action that was the context of the Fifty-First's engagement in the late afternoon of September 19. The fate of Wood's line was the initial karma of Bradley's.)

As Bradley's Brigade headed across the west Viniard field, it was not alone in defending the Union cause on the right wing. There was no lull in the fighting, no between-desperate-rounds, while the four regiments of Bradley's Brigade marched. There was a line in front of them. There were comrades, fighting, trying to stay alive, and hang on to terrain across the road. Who were those men, worn out with fighting, with whom Bradley's men were now to make coalition? Twenty minutes earlier division commander, Thomas Wood himself, pulled together the remains of his own regiments of Buell's Brigade and as many of Carlin's men, of Davis' Division, as he could. In this frantic army building—the Federal right and the well-being of the Federal army was at stake—he was assisted by Carlin, Buell, and various of their regimental commanders. Wood's line was make-shift, and it's difficult to identify its components and their relative placement. The Twenty-Sixth Ohio, at half its three o'clock strength, formed the left wing. The Twenty-Sixth Ohio was the left of Buell's formation at 3:00 p.m. It was on the left now again at 4:30 but considerably right of its first position, the old left of 3:00 p.m. Lieutenant Colonel William Young, commanding the Twenty-Sixth, called Wood's formation "our little line", and identified those making common cause with him on the left: a few men of the Thirteenth Michigan and another fragmentary regiment, he wrote, "...of, I think, Davis' division, and a few brave spirits of various regiments under the immediate command of General Wood" (OR 30/1, p. 671). Major Charles Hammond reports the presence of his regiment the One Hundredth Illinois in the little line (OR 30/1, p. 659), and the "fragmentary regiment" was the Thirty-Eighth Illinois of Carlin's Brigade, which now joined some few men to the line that was returning to the Viniard farm, where the regiment had been incinerated for two hours. That was Wood's new left—except for the extension of it that would, as we will see, come forward with Sheridan (pp. 533, 529).

|

Embree of the Fifty-Eighth Indiana reported that he formed into line of battle with the Eighty-First Indiana of Carlin's Brigade on his right. Calloway, commanding the Eighty-First Indiana, at its anchorage on the rise in the east Viniard field, reported too that the Fifty-Eighth Indiana "came up on our left" (OR 30/1, p. 524). Thus, the right of Federal line, as Wood pieced it together, was held by Calloway's Eighty-First Indiana, already in position. Next was Embree's Fifty-Eighth Indiana, which advanced with Wood. Calloway observed Carlin, his brigade commander, "still to the left of the Fifty-eighth Indiana Volunteers, most fearlessly moving forward a body of troops I then supposed to be the remainder" of his brigade (OR 30/1, p. 524). The Twenty-First Illinois, of Carlin's Brigade, placed itself, a remnant, in the little line. Chester Knight, the senior captain of the Twenty-First Illinois, reported that the regiment advanced with the Fifty-Eighth Indiana on its right and the Thirteenth Michigan on its left. Calloway misidentified some of the units involved in the back-and-forth on his left (for example, crediting solely the One Hundred First Ohio with recovering Estep's guns), but he was no doubt correct when he identified the Twenty-First Illinois in the line to the left. He was, after all, the major of the Twenty-First, in command of the Eighty-First Indiana only for the two days of Chickamauga. We can give Wood's battle line at least a hazy sequence then: Buell's Fifty-Eighth Indiana on the right, Buell's other regiments on the left, remnants of Carlin's units in the middle. (The regiments of Buell's Brigade had suffered varying fates, the brigade having split in two. The Fifty-Eighth Indiana, advancing after the other regiments had been pushed back, had moved to the right and rear along with a part of the One Hundredth Illinois to support Cullen Bradley's Sixth Ohio Battery. For an hour they had done so. Embree reported that the rest of Buell's command "seemed to have formed in some other part of the field not far distant [OR 30/1, p. 662].) The line was built, the line was cobbled. Away they went, agonized for the outcome—against hope hoping to protect the flank of the army. Lieutenant Colonel Young wrote, "Under the immediate command of General Wood, we charged across the [west Viniard] field." The line waxed as it went; Young wrote, "We were joined as we charged by many brave fellows who had staid in the ditch, and a few others who had remained by the fence" (OR 30/1, p. 671). Now as Wood's line reached the road and the east Viniard field, the Twenty-Sixth Ohio's center was "at a point where the Eighth Indiana Battery had formerly stood"—the Viniard door yard. Carlin said his men—"due to want of regimental organizations", never made it beyond the road (OR 30/1, p. 516), but some of them did, and ground was regained and Wood's little line crossed the road (not Wood's horse though, which was shot once, then twice, and killed in the crossing). Again Estep's battery crossed into the east Viniard field, 100 yards (Estep, p. 677) south of its first position, its 3 p.m. position at the Viniard door yard. Wood had an infantry line and a battery in the east Viniard field. The Eighty-First Indiana was in its strong afternoon position at the south edge of the east Viniard field, giving Wood a post to tie his line to. |

|

The pendulum swung, and swung again. Even as Young's left wing crossed the ditch west of the Viniard farm yard—even before crossing—Confederate fire from a hundred yards away was killing the men of his color company. "Our little line staggered for a moment under the concentrated fire opened upon it from the woods" wrote Young, but it crossed the road and entered the woods where the left sections of Estep's guns had stood at 3:00 p.m. "and nearly parallel to our original line" (OR 30/1, p. 671). Instead of fronting straight east, the line had a slightly oblique angle, fronting also with a bit of north—to meet Confederates in the woods, who came from east and north—the woods at the school house were not secure—and because the whole line stretched at an angle across the east Viniard field with the right of the line, where it tied to the Eighty-First Indiana, further east. The line fought its way into the woods, but was hit by a "rapid cross-fire on" Young's left flank. Young changed formation ninety degrees so that his line faced north and backed up to the fence which ran along the Viniard-Alexander road, north of it. There the line held—by shooting into the face of advancing Confederates.

But Confederates in the woods, were not the extent of the Confederate hostility. East of the east Viniard field another attacking line stepped off, intent upon again gaining the road. Wood reported, "Scarcely had the lost ground been repossessed than the enemy emerged from the woods on the eastern side of the corn-field, and commenced to cross it. He was formed in two lines, and advanced firing. The appearance of his force was large" (OR 30/1, p. 633). Against this line and the Confederate forces in the woods to the northeast stood Wood's little line—single, a thin blue line, strung across 250 yards of front. Young, noticing the "new" Confederate line "500 to 600 yards" distant, changed front to the east again, and had his men lie down. Young, trying to hold the left end of Wood's line, was in a unique position to see the gathering coordinated storm of the Confederate attack: Robertson and Trigg advancing, primarily across the open field from the east, and Benning from the northeast in the woods where the Confederate force was already close enough to thwart Young's advance and force him to adjust his line.

In the face of this coordinated Confederate counter, which operated on two fronts and now pushed ahead in the east Viniard field, Wood's advance stalled. Once more the Federal right was in the dire strait of renewed attack around the Viniard farm. Wood's line was not able to advance beyond the crest of the rising ground in the east Viniard field. Calloway's adopted Eighty-First Indiana still anchored the line on the right, but on the left where the Confederate pressure came both from the field in front and from the woods on the left, Young had pulled the line back to the road. Estep's Battery was still on the crest of the rising ground firing east and northeast, across the field and into the woods, but the supporting line of infantry was punctured—by the rifle fire of Confederate line advancing from the east—and starting to leak rearward, pushed by the momentum and awesome aspect of the Confederate attack. Estep's gunners still operated their guns but were starting to look to their own safety, keeping an apprehensive eye on the weakening left that would allow enemies to come in behind them. Confederates in line in the woods around the school house continued yet to deny, by rifle fire, the eastward advance of rallied groups of Heg's (now Martin's) Brigade. For the first time in the afternoon Confederate artillery got south far enough to help Confederate infantry in the Viniard fields though it was weak in comparison to the power of the conglomerated Federal batteries (Report of Cortland Livingston, OR 30/1, p. 851). As Bradley's Brigade formed hurriedly 400 yards to the west, the contest in front of them was just turning, again, into a losing battle.

TopGoing in to the Fight

Crossing the West Viniard Field

The approach thru the west Viniard field (click for larger view)

The approach thru the west Viniard field (click for larger view)

The "Historical Memoranda" of the regiment recounted that Bradley's Brigade "was hurled right into the face of the enemy" (Illinois State Archives, Springfield, Illinois). Henry Weiss of the Twenty-Seventh Illinois wrote, "We go to where the din is loudest. Ah! the wounded meet us at every stride. Men with all sorts of wounds are lying or leaning against trees on every side. We meet with refugees from the field, parted from their commands." Marching through the woods to the west Viniard field, the men of the brigade came up in the rear of Wilder's position, up behind Wilder's barricades, the Viniard's west fence, and the suffering flotsam of regiments that had fought, been attacked, and counter-attacked throughout the afternoon. George Juncker of the Fifty-First, without benefit of the Official Records, knew they were entering the battle behind Wood: "I say this," he wrote, "because we had passed by wounded men who said they belonged to that division."

For the men in line, there was "a strange thrilling feel, a feeling that you were standing near the verge of the grave. There was fear that you could not endure the terrible ordeal, dread that you might not be able to do your whole duty... They open their cartridge boxes and there is a moment of suspense. The faces are all white as death along the line; there is a sinking feeling of the heart, a catching of the breath..."14 Allen Gray, with the cat that adopted him at Tullahoma perched on his shoulder, stooped to take the rifle from a wounded man—commissary sergeant, he had none of his own. (Photograph: where regiment formed, west Viniard Field)

The Crossing: The First 90 Seconds. Bradley's Brigade formed its lines just west of the western edge of the west Viniard field, behind Wilder's position—"in the thick underbrush," wrote Sylvanus Atwater of the Twenty-Seventh. The Fifty-First formed into battle line "on the right by file [Yuncker]," a common oft-practiced maneuver for the purpose of moving quickly, sequentially, company by company, man by man, from a marching column into an advancing line (an animation depicting on the right by file). The Twenty-Second Illinois filed into position in front on the left, the Twenty-Seventh Illinois in front on the right. The Fifty-First Illinois formed the second line on the left. The Forty-Second formed the second line on the right. The Fifty-First, being on the left rear, was the last to pour into line—and its left companies, the last of the last. Lt. Col. Raymond's After-Action Report reported that the Fifty-First was still completing formation when the command "Forward!" came. The brigade and the regiment moved. The men of the three companies of the Fifty-First on the left broke into a run—through "timber and underbrush and over a rail fence"—to keep up with and complete the regimental line. Raymond was thus still dressing his line when the brigade moved into the west Viniard field. Atwater wrote home, "The word forward was given; we scaled the fence and charged them with a shout which had not been repeated since we had used it with such success at Stone's River."

Four hundred yards to the east, unknown yet to them, lay the end-point—the high ground of the east Viniard field—of their hurried march. The rise in the east field is visible from the western edge of the west field (one looks from relatively high ground across the shallow "valley" of the ditch to relatively high ground); the smoke from the furnace of battle obscured the further distances, but the men of the regiment could see the trees around the Viniard place, and the discharges of Estep's guns on the rise punctuated the distant smoke with fire. The two-regiment brigade front extended 175 yards, a tenth of a mile left to right, as the brigade crossed the field. The first line was 65-75 yards in advance of the second. At double-quick time, it would take the brigade two minutes to reach the road (165 steps/minute, 300 yards).

As the regiment came out of the trees and over the fence, Yuncker's limited view in the battle line caught sight of "a field in front and a battery or part of one on the field. The rebels in the edge of the opposite timber were in plain view," Yuncker's enemies in control of the Viniard grove to the north of the farm buildings and likely of the farm buildings themselves. Sheridan and Bradley on horseback were "in front of the right of my regiment (Fifty-first Illinois)." Sheridan was "watching the enemy through his field glass." As they moved forward at "shoulder arms", Sheridan "personally" gave them the weary admonition to "keep cool and fire low" while trying to kill and stay alive.

The brigade moved across the west Viniard field. Crossing the field discovered a bedlam to the brigade—the sequentially layered residue, the martial strata, of two and one-half hours see-saw fighting—dead and wounded men of Carlin's Brigade, dead and wounded of Buell's Brigade, dead and wounded of the Confederate brigades. There, officers rallied men to reform units, Federal artillery fired across the field into the woods and fields beyond the Lafayette Road, wounded Federal and Confederate soldiers sought shelter along the ditch. Ambulance crews retrieved wounded men. Killed men lay on the ground. Young of the Twenty-Sixth Ohio described being in hell at the ditch, "Many wounded had already sought this as a place of refuge from the storm of musketry, grape-shot, and shell now sweeping the field from the edge of the timber on both sides. Many others had also rallied here from the troops that had retreated over my line.... Many of my own men had rallied here when the line first fell back and were fighting bravely from the imperfect cover the shallow ditch afforded... [My line] was flanked and raked with murderous fire. Many of the wounded were again struck, even the second and third time" (OR 30/1, p. 671). Such was the ditch—teeming with injured life, a hiding place, a first aid station, a staging ground, a last rite, a morgue—as Bradley's men crossed it. Bradley's officers worked to keep the lines dressed, to maintain intervals, to prevent the individual retreat to the rear of individual soldiers. The two flags of each regiment were out in front in the hands of the color bearer and the care of the color guard. The lines, the movement, the cheers, the colors, the quick steps of the charge hastened the men across the field despite their trepidation—despite the blanched faces, despite the bodily suspense. A few men gave up, their fear stronger than their forward intention, and fell back—or tried to fall back. Some were turned back to the front and hurried to catch up with the line, but a few eluded officers, the encouraging admonitions of their line-mates, and the file closers, and found their way back into the woods at the west edge of the field. Henry Weiss of the Twenty-Seventh Illinois named two men of his company who sought safety at the rear, James Rutherford and Joe Brown. There were others throughout—men not quite able to bite back every rising qualm and let go the world of relations—but except for Rutherford and Brown they are nameless.

On the brigade's left, 150 yards off, Heg's men were rallying and trying again to cross back across their northern portion of the west Viniard field, north of Lilly's battery. Mons Grinager of the Fifteenth Wisconsin reported that "Sheridan's division advanced on our right... We twice tried to recross the field, and succeeded the second time in getting as far as the log-house on the south side of the field" (OR 30/1/, 533. Grinager swaps north-south with east-west).

The Crossing: The Last 30 Seconds. Once descended into the marshy ground at the ditch and to the ditch, Bradley's 1300 marching men could no longer see beyond the road where they were headed. In front of them was the incline up to the Viniard yards and orchard and the road, the incline steeper at the left of the line than at the right. Four hundred yards to the east, advancing westward through the east Viniard field toward the Lafayette Road, coming up the rise from the opposite direction, the double lines of Confederate forces came foward, closer, firing. Between that double line and Bradley's double line, Wood's little line was engaged, trying to hold back the Confederate advance and protect Estep's Battery, so his guns could remain engaged.

Though Bradley's men had, for the moment, some cover to the front, they had little to the front-left where Heg's men were struggling to gain the road, Young's Twenty-Sixth Ohio was in search of a position that it could maintain. this line of cover to the front left was necessary to protect the Federal line—whether it was Wood's line or Bradley's line— from being flanked on the left and having to make war on two fronts. The Twenty-Sixth Ohio, at the Viniard farmstead, braced itself for the clash. Young reported that Sheridan's men came up behind and started firing into his position from the rear. He went on, "I promptly moved back to the fence and awaited the onset;" (OR, 30/1, p. 671). The Twenty-Second Illinois and Fifty-First Illinois on the left, began to feel enemy fire from the trees to the north and east of the Viniard Farm. The left wing of the brigade formation suffered more as the first line neared the ditch. As yet, none of Bradley's men had fired a shot. Confederate men of Benning's Brigade, withdrawn from their advance in to the west Viniard field, pushed forward again and filled it where Young pulled back. They hid in the Viniard farm grove east of the road and lay secreted behind the fence and trees and in the streambed, to the north of the east Viniard field, holding their fire. The brigade's first line crossed the marshy stretch of the ditch. The men of the left and center companies of the Twenty-Second Illinois, struggling to maintain its line, trudged up the incline—steeper at the left of the line than at the right—seventy-five yards up to the Lafayette Road. The Fifty-First Illinois, in the second line, following at double-quick time, traversed the ditch. In some stretches the ditch deepened to a small stream; there men had to leap to cross the water. The charge maintained its pace and rhythm, despite the first casualties in the Twenty-Second Illinois—and soon the Fifty-First.

At this critical command moment, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Raymond's black horse, presented to him by the citizens of Chicago, (sensibly, and now filled with premonition) took fright and galloped crazily off—carrying Raymond—seeking shelter from the storm. Raymond soon returned to the fight—in time for the black horse to be killed underneath him—but for the nonce Major Charles Davis and Captain John McWilliams of Company E, the regiment's senior captain, commanded the regiment in its advance. Bradley was everywhere keeping the brigade aligned as it moved forward. Moments after Raymond's horse abdicated, as the Fifty-First rose the incline west of the road—the Twenty-Second Illinois, ahead in the front line, already at the road, already with men down in the road—"advancing over that open field under the withering fire from the enemy in the woods," as John Johnson told it, "we began to falter"—Bradley galloped up in front of the regiment, shouting through the din, "Forward 51st! All that don't are cowards." With that, Johnson wrote, the regiment "went forward as if touched by the magic wand of Aladdin" (Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, Springfield, Illinois).

Allen Gray marked off the advance of the regiment and the brigade, "...by the right flank through the woods - over a marsh - up a ridge - past Vinyard's log house - crossing the Lafayette road into an open field...strewn with the dead and wounded of friend and foe." The cadenced forward movement of the brigade prevailed—despite fire from the groves to the left—in the charge up the incline, across the road, and into the east Viniard field. Bradley's men gained the crest of the rising ground with the first Confederate line in the cornfield still 150 yards off. But, already the Federal coalition line in the field was in serious danger from Benning's men,"lying down in the woods,"as George Estep reported; he was firing on them, but they were killing his horses and wounding his gunners with their fire. Estep decided to pull back across the road OR, 30/1, p. XX).

Bradley's line came up with Wood's now even littler line, which was giving back"edging back toward the road"under the attack of the Confederate lines from the east. Wood wrote merely, "Fortunately reinforcements were at hand." Some of the regimental commanders in Wood's line said they were "relieved" by Sheridan and Bradley. Carlin, of Davis' Division, wrote in his report, "A brigade of Sheridan's division took the front." (Carlin also reported that the brigade was soon driven back, which was not the case, OR 30/1, p. 516; Carlin's "Military Memoirs", National Tribune, April 16, 1885, repeated this). Sylvanus Atwater of the Twenty-Seventh Illinois wrote that Wood's line was giving way. Jonathan Miles, colonel of the Twenty-Seventh, reported that at the time the Twenty-Seventh advanced into the east Viniard field, the infantry line supporting Estep's battery "...had almost abandoned the position entirely." Estep thought so. His gunners were leaving the guns and heading back toward the Lafayette Road. Some of the men of Wood's line fell in with Bradley's line and moved back across the field. Others, relieved, vanished back through Bradley's formation across the road. Some reshuffled themselves in the line—pushed back, they pushed back forward. Calloway, major of the Twenty-First Illinois and in temporary command of the Eighty-First Indiana, said sixty men of the Twenty-First Illinois—among them, Eaton, Gross, Russell, and Jones—"rallied upon the Eighty-First Indiana" in the end phase of the east field fight (OR 30/1/, p. 524)—thus was Little Gibralter strengthened and thus did Carlin's men, without Carlin, work out their own salvation, and for that of the Union. Into this melee marched the Fifty-First Illinois and its three sister regiments. The line in front of them was breaking at the left and losing men rearward at the center; diehards were moving to the right to hang on with the Eighty-First Indiana.

There were casualties in the Twenty-Second Illinois and the Fifty-First from the time they crossed the ditch eighty yards west of the road, and more the further they advanced. Besides casualties on the left, Confederate bullets were taking their effect all along the front line. There, in the Twenty-Seventh Illinois forty-five men were wounded; two were killed. Jonathan Miles, in command of the Twenty-Seventh Illinois, in the front line at the right, had his horse killed underneath him. Nonetheless, despite the casualties, this first Federal charge across the road and onto the crest of the rising ground was achieving its purpose. Atwater wrote, "The enemy at first gave way in the open field." Miles wrote that his regiment climbed "up a gentle slope, where it met a fierce fire from from the advancing enemy, whose advance was checked and they repulsed" (OR 30/1, p. 597). The front line of the Twenty-Second and the Twenty-Seventh, despite casualties in the Twenty-Second, along with the oblique fire of the Eighty-First Indiana and the men of the Twenty-First Illinois who stuck to them, delivered a hot enough fire to "check" the Confederate advance and drive their lines back. They drove all before them, Raymond reported, until they passed a skirt of woods on their left.

Viniard's Grove: Until We Passed a Skirt of Woods on the Left. Period maps show a stand of trees, a grove, across the road from the Viniard house in the east field. The grove lies just south of the intersection of the Viniard-Alexander Road with the Lafayette Road. H. V. Boynton, who commanded a regiment at Chickamauga and who played a pivotal role in the creation of the national military park, wrote in the first park guide, "The grove in the field directly east of Viniard's was dense, and extended from the present eastern limit to a point on the La Fayette road opposite the house. There was also a strip of timber along the west of the road in the vicinity of the Heg Monument" (H. V. Boynton, The National Military Park Chickamauga-Chattanooga. An Historical Guide, With Maps and Illustrations. Cincinnati, Robert Clarke, 1895). (Click: Map with Viniard's Grove) The Viniard grove extended along the Lafayette Road as far south as the house. It was just to the front (east) of this grove that Buell, at 2:45, first aligned the center of his brigade to advance. Perry L. Hubbard of the brigade battery, George Estep's Eighth Indiana Light Artillery, recalled, "On Sept. 19 we were moved to the left and took a position on a ridge in the door yard of a double log house" (L. Hubbard, 8th Indiana Light Battery, National Tribune, June 6, 1907, "The Capture of the 8th Ind. Battery.").13 (Buell, "The Twenty-sixth Ohio and a part of the battery were in heavy timber, while the other regiments and remainder of the battery were in open ground," OR, 30/1, p. 654; also Estep's report, "left half o my battery resting in woods and the right in an open field," p. 676.) When Embree's Fifty-Eighth Indiana advanced through the grounds of the Viniard farmhouse, the left of the regimental line moved through the dense Viniard grove. Chaplain John Hight of the regiment wrote, "The right of the 58th was in the open space, the left Companies advancing in a little skirt of timber" (p. 181). The "skirt of timber" was the Viniard Grove. It stretched north-south along the east side of the Lafayette Road north to the Viniard-Alexander Road. It was fifty yards in breadth from west to east and was bounded by fences. This was the skirt of Woods that lay off the Fifty-First's left as they advanced and which figured in Raymond's after-action report.

The line of the Twenty-Second and Twenty-Seventh Illinois regiments advanced to the crest of the rising ground. The Fifty-First, trailing the Twenty-Second, had advanced across the road into the east field 25 to 35 yards. The brigade fought; only the Forty-Second Illinois, in the second line on the right, was largely spared in these initial moments in the east field—largely but not altogether for the Forty-Second also suffered casualties. Suddenly there was a fierce increase of gunfire from the left, from the woods north of the Viniard-Alexander Road, and, closer to the Fifty-First, from the Viniard Grove, south of the Viniard-Alexander Road (40 yards distant). Atwater wrote, "As we advanced they got a flanking fire on our left wing". The fire was close and intense, "murderous and enfilading," Raymond called it. Especially, the Twenty-Second suffered as it was under attack from front and left, but the rate of casualties in the Fifty-First was almost equally heavy because of the close fire from the Viniard Grove.

The vulnerability of the Federal line from the Viniard Farmstead to the log school house was exposed. In the east Viniard field the Confederate forces had to fight their way forward and were almost powerless against the right of the Federal line held by the Eighty-First Indiana—and its allies—in its lair of terrain. But in the wooded ground around Viniard's and in the woods north of the Viniard-Alexander Road, Confederates were strongly positioned facing west toward the Lafayette Road and south toward the Viniard-Alexander Road. The left of Wood's little line was forced back at least to the Lafayette Road there and Heg's units were trying to maintain a toehold at the school house. By marching into the east Viniard field Bradley's Brigade uncovered itself and marched into a flanked position. The right of the Federal line was strong, by position and relatively in numbers over against their Confederate enemies at the south side of the Viniard field. The left, on the other hand, was weak, with a Confederate salient lowering in the woods and able to bring greater numbers to bear at the intersection of the roads near the Viniard door yard—Benning, Trigg, Robertson.

In the Fifty-First, Companies G and K were on the left of the line, and men were soon down. The line there crumpled and became a tangle of the dead, the wounded, and the still fighting. Lieutenant Henry Buck, in command of Company K, was hit in the forehead and died without uttering a word. Lieutenant Albert Simon, at the left end of the line of Company G, was shot dead. Charles Trust, William Patterson, and Robert Stack, all of Company K, all fell dead within minutes. Edward Burns was severely wounded in the leg. He crawled 250 yards toward the rear, dragging his broken leg, across the road, down the incline, toward the ditch, far enough to be safe from rifle fire. Charles Wagoner, Thomas Cooper, John Cochran, Archibald Cook, Thomas Robinson, and Christian Wagner of K were all struck down, wounded. Wagner had only a few days to live. Calvin Edwards, Frederick Thompson, and Clark Wicks, Herman Schubarth, Julius Gesche, and John Sauerman were hit. Sauerman lived on for another several months (the angel of death, patient, waiting for him at Atlanta). Company K went into the fight small in number, and after a few minutes of fighting, only eight men of Company K were whole.

In Company E, toward the center of the Fifty-First's regimental line, Richard Bilby was killed. Another dozen men of the company were wounded. Mathew Romine was shot with buckshot in the chest; the shot penetrated his right lung. He lay on the ground, bleeding. "Pale and sick, he begged to be helped off the field." His friends told him to wait until the fighting lulled. John Johnson wrote, "A small Irishman, Pat Ferril [Farrell] of E, while making this charge, was struck in the forehead. We were told by some of our comrades that they saw him on the field, his brains oozing out."

TopMore Fighting

Lie Down! - The Death of John McBride. Bradley, seeing his brigade damaged by wounds and death, ordered the four regiments to lie down. John Johnson of Company E recalled, "Col Bradley shouted. 'Lie down!' We did, without any special persuasion. He sat there receiving the full fire of the enemy, reminding me of the pictures I saw of the first Napoleon Bonaparte, in my boyish days."4 Bradley was too easy a target for the Confederate shooters. He was struck twice and was fortunate to escape becoming a dead man. His assistant adjutant general Otis Moody was wounded at the same moment; the wound shortened Moody's life down to another eight hours.

John L. McBride, known among friends and family, for his eighteen years, by his middle name Lucian, was killed just after Bradley ordered the men to lie down. "He raised his head and as he did so a ball struck him in the forehead." A comrade or two crawled to him and dragged his body back toward the road to a "log"—an orphaned fence rail—where they could find him later, once the bullets stopped. They came for him, seven months later.

And so the swell of injury rippled through the companies of the regiment, and they fought back, shot back—keeping close to the ground, rolling onto their backs to load, rolling over again to fire, inflicting as much damage as they took. The 400-500 rifles of the two regiments drove Benning's Brigade back deeper into the trees. The fighting—the mutual slinging of minie balls, the mutual destruction of enemies—continued. It lost slightly of its sting with the Confederates more distant in the woods and the Federals flat on the ground. Yuncker wrote, "We lay flat, loading and firing at will for some time. All seemed to go well, though the bullets flew thick and close, and many an officer and private fell." Mel Follet of the Forty-Second Illinois, which was in the second line and on the right, wrote in his diary, "We drove them a short time." Despite heavy casualties in the Twenty-Second and Fifty-First the brigade stalled the Confederate attack and was pushing the enemy lines back.

It had been ten minutes since the brigade crossed the road.

Enemy attack energy was hardly expended. There was a lull, but then enemies in drab—Benning's men—loomed up out of the woods, in a counter-charge. In a trice they were over the fence and crossing the Viniard-Alexander Road, falling with bullets upon the brigade left. Mel Follet wrote in his diary, "...they rallied, gave us fits." (Follet was wounded in the left leg.) Atwater wrote, "The enemy charged in turn from a piece of timber on our left." Estep reported that the Federal infantry was "charged by the enemy en masse who came yelling like devils." The gunners left three guns behind and fell back across the road. Yuncker recalled, "A yell of triumph from the rebels caused us to look to the left, where we saw our line falling back and the rebels directing an oblique fire into our left flank. This, added to the storm of bullets from the front, made it seem as if the air was literally filled with zipping, shrieking minies and bullets, and we hardly dared to breathe for fear of inhaling bullets, though we laid low and as flat as soldiers only can do when necessary."

The conflict flared, as the Twenty-Second and Fifty-First faced the Confederate charge; the fighting was fierce, with the enemy lines visiting many, many casualties upon each other. "In proof of the severity of the action on the 19th," the Illinois adjutant-general capsule history of the Twenty-Second recorded, "the Regiment lost 96 men in less than ten minutes, most of whom were down." They held on. Some of the wounded worked their way back toward the right of the Fifty-First, which was busy to its left, shooting left-oblique. The Twenty-Second, which was sturdy at Belmont and Stones River, was sturdy now. Despite horrific casualties, they did not stampede back through the line of the Fifty-First—indeed, most of the wounded men were "down", as the capsule history put it—down and therefore able only to go at a crawl.

Before the Confederate charge could be checked and beaten back, men of the left company of the Twenty-Second found themselves on the wrong side of the Confederate line. Confederates came from the left and in behind them, between the Twenty-Second Illinois and the Fifty-First. Atwater wrote that the enemy "succeeded in capturing nearly a whole company of the 22d Regiment Illinos Volunteers." Atwater's estimate is an overstatement, but certainly the Twenty-Second had a company's worth of men taken captive during the two days of Chickamauga—more even but not an entire company, whole. Company C had a high proportion of captives to killed-and-wounded; it may have held the left of the line at the time of the Confederate charge (Lieutenant Robert Clift, "List of Killed and Wounded in the 22nd Regiment," Alton Telegraph, October 16, 1863). The fighting was very close, so close that the lines were tangled. Bradley's Brigade, too, plucked prisoners from the Confederate fighters.

[A Parenthetical Placeholder: Falling Back on the Left. The key to the last fight at the Viniard farm on the 19th, the fight Bradley engaged, is what happened on the left of the brigade line. When the brigade advanced into the field either there was no support on the left or, more likely, soon after the advance into the field the support on the left was driven back under pressure from Confederate forces in the woods around the school house and across the Viniard-Alexandaer Road north of the Viniard dooryard. Young said that, as Bradley's Brigade came across the west Viniard field, he, aware of the two-pronged attack that threatened, pulled his men back to the fence, but, in the absence of the map his report referred to, it is difficult to know which fence the Twenty-Sixth Ohio moved back too. Young further said that shortly thereafter a Kentucky regiment—of Sheridan's Division, he thought—was moving obliquely across his front and was driven back into the Twenty-Sixth Ohio. Young does not say whether the oblique movement was moving northeast or southeast. Sheridan, of course, had no Kentucky regiment in his division—though the Fifty-First Illinois might well have moved obliquely across his front, if, that is, Young had pulled back his forces at the Viniard Grove, but indications are that Young was north of that, slightly further up the Lafayette Road. Did Young refer to one of Sheridan's Illinois regiments or was it Heg/Martin's Kansas regiment, which might have been moving southeast across Young's front? Neither Harker's Kentucky regiment nor Barnes' Kentucky regiment could have been in front of Young.

This whole matter matters because the support, or fading of support, on the left determined the fight that the Fifty-First and Twenty-Second Illinois regiments fought. —]

The First to Reach the Ditch. The Twenty-Seventh Illinois, in the front line to the right, south, of the Twenty-Second, maintained their line unbroken for the thirty minutes they inhabited the brigade's forward line on the crest of the rise. But the lines of the Fifty-First and Twenty-Second were no longer unbroken. The left wing of each of the regiments was laced with casualties, but they still held their ground. The Twenty-Second was beleaguered with war on its front and left. The Fifty-First had to contend with Confederate skirmishers who were still firing from the Viniard Grove. The regiment was ordered to fall back across the road to rebuild its line at the ditch with a view to clearing out the skirmishers and extending the line to the left.

John Johnson heard the order to retreat passed down the chain of command:

It was not long till he [Bradley] was wounded. He gave orders to retreat. I was lying flat on my back loading my rifle. I finished loading before starting to the rear. Just then I saw no need of great haste. On raising to my feet, changed my mind, found the boys had considerable start. Think I outran every man in the Reg but one in the race back to the ditch. Got over the two fences on either side of the road. Could never remember getting over those fences. Only time in 13teen battles I was in that I did not know all I did and what occurred around me. The man that outran me, in the race, was Mat Romine, Co. E. ....When we took to our heels, Romine sprang up and was among the first to reach the ditch.

Sheridan, who had advanced with his staff out toward the ditch at the southern spaces of the west field, where he could look to the northeast and see the action in the east field, turned and headed back for the safety of Wilder's barricades, in case his, Sheridan's, lines should be pressed back and the deadly action come back across the ditch.

George Yuncker recalled, "When at last orders were given to fall back, there were but few of the left wing who had legs able to carry them back." But Romine, gunshot to the lungs, who had lain on the ground and begged for help, now with some sort of extramundane battlefield energy, found his legs and was first to reach the ditch. When Yuncker himself, though, tried to get up and go, he couldn't. "After several unsuccessful efforts to run, I was not a little surprised to find a hole in my pants covering my left thigh, and found that I had no feeling in the leg and foot. I had received a couple of wounds in my right arm and hand before that cross-fire, but felt confident of the ability of my legs doing their duty when the time should come." Johnson, Romine, and the rest of the ambulatory of the regiment were in a safer space when they crossed the road and down the slope toward the ditch. The lull in the fighting even allowed for two men to help George Yuncker back to the ditch; others too. The officers hurried to rebuild the regimental line, companies shuffled their positions. The line was shorter now. The men had friends dead, and too wounded to move, 125 yards to the front, out in the east field. Many of them were hit by enemies in the Viniard Grove. The regiment's own fire and artillery help had thinned out the Confederate presence there, but it was still a source of flanking danger. As the regiment prepared to advance again across the Lafayette Road, Raymond and McWilliams and Davis, conferring, sent a small mission of three men to work their way around the Viniard farm buildings to the left. The lot fell to Pratt of Company A, who was put in command of the detachment, the short straw to Charles Nelson of the same company. We have no record of the third man's name. And, we have very little record of what happened to the three men after they entered the grove. The exchange of fire was sporadic, then hot and killing, then there was silence. The Confederate men forsook the grove and pulled back into the wood across the Viniard-Alexander Road. Pratt and his colleague returned carrying the body of Charles Nelson. By then, the renewed regimental line was moving back across the road, increasing their speed to double-quick step.

Raymond reported, "We again charged forward, and gained the fence lining the west side of the woods which skirted the crest of the ridge and maintained our ground in the front." It's not yet clear to us what woods and what fence Raymond referred to, and it's possible that he has his directions confused. His report might refer to the fence along the road at the western edge of the Viniard Grove; then, Raymond's directions are right and west is west. His report might refer to the fence along the Viniard-Alexander Road, in which case Raymond's directions are not right. This latter possibility is less of a possibility since Raymond wrote that they "gained the fence", and it's unlikely that the Fifty-First "gained" the fence in the sense of positioning their line along it. Be that all as it may, the advance of the regiment, its fire to the left, and the supporting artillery fire put a stop to the Confederate advance from the woods on the left. Raymond reported that the regiment maintained its "ground in the front, while a battery in our rear drove the enemy advancing from the woods on our left. I was compelled to crowd my left toward the right, as the fire from the battery passed through it, killing and wounding several. I also directed what remained of the left wing to fire 'left-oblique,' and in a few moments the enemy were flying from our front in great disorder."

Men of Robertson's Brigade fighting west through the east Vinaird field, taking advantage of the diversion caused by Benning's charge, got close enough to attempt capture of the Eighth Indiana Battery. Atwater wrote, "The gunners of the 8th Indiana Battery were run away from their cannon by the close shots of the enemy." Edward Crippin of the Twenty Seventh Illinois wrote in his diary, "We have an eye on the battery and go for it double quick... We arrive at the battery while the rebels are seventy five yards off, pouring a volley in to them that makes them waver. We drop to the ground, not a moment too soon for a volley from the Rebs sends a sheet of lead flying over." Nearly every Federal unit within a hundred miles claimed to have saved—or, in years later, to have recaptured—the guns of Estep's battery. The claims were compounded by the fact that Estep's battery, or part of it, was rescued more than once—and Estep's were not the only guns requiring rescue. Probably, almost every regiment in the east Viniard field lent hands to the effort of dragging the guns off the rise and back across the road—and Lieutenant Potter of the Twenty-Sixth Ohio was run over by one of the guns (Young's report, p. 677)—and the Twenty-Seventh, who had its own injured victims of the panicked horses, played a central role. Calloway, commanding the Eighty-First Indiana Infantry, gave credit to the Hundred First Ohio for the rescue of Estep's guns though the Hundred First made no such claims for itself. L. W. Day of the regiment assigned the "recapture" of the guns to Sheridan's men. The after-action report of the Hundred First Ohio makes no mention of the guns (OR 30/1, p. 527). Interestingly, Captain Mons Grinager of the Fifteenth Wisconsin Infantry, Heg's regiment, reported in his after-action report that the regiment "retook a few pieces of artillery" (OR 30/1, p. 533)—adding another regiment to the coalition of regiments close enough to lend hands to preserving Estep's battery to the Union. Though Bradley years later referred to orders ordering him to recapture Estep's battery and though historians who have concerned themselves with the event in later years write in terms of recapturing a captured battery, it is quite clear that, at this juncture of Bradley's advance, the guns never quite fell into Confederate hands—though the guns were abandoned by the gunners and the infantry support of Wood's "little line". Colonel Miles of the Twenty-Seventh Illinois reported, "The artillerymen worked their guns for a few minutes after our arrival, but they soon entirely abandoned their pieces, although my regiment was at the time supporting them in an unbroken line." The diary of Edward Crippin and the letter of Sylvanus Atwater support that sequence of events.

The Forty-Second Illinois, which was due to be incinerated the next day at the base of the Widow Glenn's hill, was blessed yet on September 19. In the second line, south of the Fifty-First, they were largely sheltered from direct Confederate musket fire by their position, most distant from the left flank fire and most distant from the front fire, especially after the men of the four regiments began to carry on the fight from prone positions. Simonds of the Forty-Second wrote, "We come near being repelled but stand our ground." And, so it was. The left of the brigade line was weakened and bent back, but the Confederates withdrew into the woods again. The fighting continued, now smouldering, as compared to the conflagration of a few minutes before. Less than thirty minutes had passed since the brigade stepped onto the Lafayette Road.