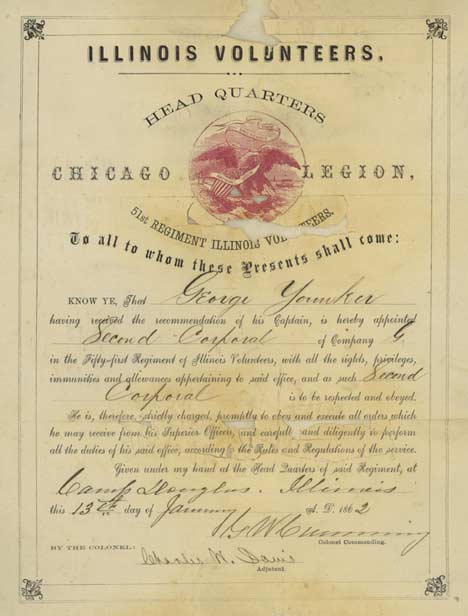

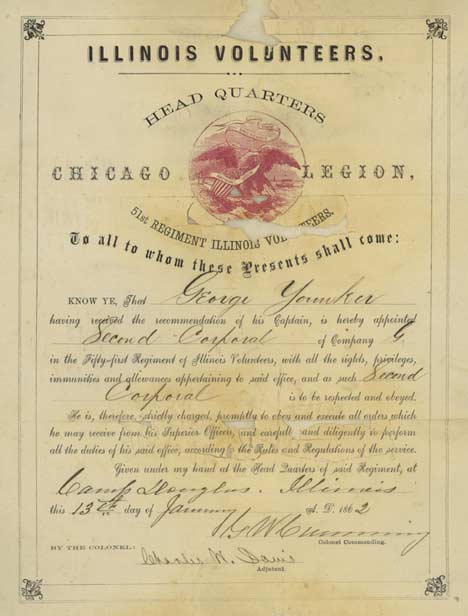

Appointment, Second Corporal, George Younker Papers, C2100,

Western Historical Manuscript Collection-Columbia, MO.

Juncker's mother died in about 1843. Soon thereafter, Juncker's father migrated with his children to the United States, landing first in New Orleans and then moving on to Ohio. George wrote in an 1890 pension deposition, "I was born in Alsace, France, on July 13, 1833, came to this country about the year 1843, with my father, and settled at Fremont, Sandusky Co., Ohio." The 1850 census found father Nicholas living in Sandusky County with George's brother (also) Nicholas, Nicholas' wife Christina, and a band of children. George himself, just turned 17, was working as an apprentice to shoemaker Philip Dorr in the town of Fremont. He was a member of Dorr's household. In 1856, Yuncker began to work as a journeyman shoemaker—his journey taking him through Ohio, Michigan, Chicago, and other parts of Illinois. In 1859, he settled in Kankakee (Kankakee County), Illinois and continued his trade. There, Yuncker married Emeline Flucke.

George Wentz (first captain of Company G) enlisted him (in Kankakee) for service in the Fifty-First on October 15, 1861. In the formation of the regiment at Camp Douglas at the end of 1861/beginning of 1862, Yuncker was made second corporal of Company G (see document at left). On August 22, 1862, when the regiment was strung out through northern Alabama guarding the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, he was promoted to sergeant.

On May 3, 1862, the Fifty-First Illinois, along with its brigade and the rest of John Pope's army, advanced several miles to Farmington, Mississippi and participated in an engagement that drove Confederate forces out of Farmington and promised to be the prelude to a general advance on Corinth, but May 4th saw a heavy and constant down-pour, and the opposing armies sank back into the mud. Charles Merrick, captain of Company G, said that Yuncker became exhausted with marching and then lay out in the rain and fell ill. Merrick said that afterward he sometimes had to help Yuncker along. Yuncker himself wrote, "I laid in a furrow on the night of May 4th, 1862, and the next morning I was unable to rise, and was taken to the hospital at Hamburg Landing... from this time I suffered with rheumatism whenever I got wet." When Yuncker was promoted to sergeant, his company-mates nick-named him "Limping Sergeant". Yuncker returned from the hospital at Hamburg Landing but was again taken ill in late 1862 and sent away to Federal convalescent camp at Nashville on December 24, 1862, a week before the great battle of Stones River near Murfreesboro. Juncker, limping, returned to the regiment to stay on April 4, 1863. On July 31, 1863, he was promoted to third sergeant.

Yuncker "missed" the Battle of Stones River, but he was in the thickest of the fight at the Battle of Chickamauga in the late afternoon of September 19, 1863 as the regiment fought at the Viniard Farm. The Fifty-First came under a "murderous and enfilading fire," as Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Raymond reported and suffered over a hundred casualties in less than thirty minutes. Yuncker wrote his own account of that horrific fight in the east Viniard field: "The air was literally filled with zipping, shrieking minies and bullets, and we hardly dared to breathe for fear of inhaling bullets, though we laid low and flat...Officers and men rolled over and shot; [they were] mutilated in all shapes. When at last orders were given to fall back, there were but few of the left wing who had legs able to carry them back. I remember distinctly that mine failed for the first time to do me that favor. After several unsuccessful efforts to run, I was not a little surprised to find a hole in my pants covering my left thigh, and found that I had no feeling in the leg and foot. I had received a couple of wounds in my right arm and hand before that cross-fire, but felt confident of the ability of my legs doing their duty when the time should come. Fully realizing now that my leg had gone back on me, I lay still..." (National Tribune, August 30, 1883). Two regimental comrades carried Yuncker from the field back to a field hospital. Yuncker's service records described the physical damage he suffered: the most severe wound was in the left thigh; the ball splintered the bone and damaged the sciatic nerve. Besides that, the first phalanx of the fourth finger of his right hand was shot through and left an almost boneless upper finger. Too, another missile lodged in his right arm near the shoulder. And, yet a shell fragment inflicted a severe flesh wound of the left buttocks "with considerable loss of flesh." Yuncker had other minor, comparatively negligible wounds. The 1884 biographical sketch in History of Randolph and Macon Counties said Yuncker "was wounded no less than seven times, being as he was though shot all but to pieces." Yuncker matriculated through Federal military hospitals like other of his critically wounded comrades: first to besieged Chattanooga, then Bridgeport, Alabama, quickly on to Nashville (admitted November 14, 1863), and to his ultimate hospital destination to the Marine U.S.A. General Hospital in Chicago (admitted January 13, 1864). For six months Yuncker recuperated. He kept all his limbs and digits, for better or worse. The physician at the Marine General Hospital who made out Juncker's disability-discharge certification on June 9, 1864 stated Juncker's level of disability as "total."

After the war, Juncker on crutches returned to Kankakee. He applied for and received a government pension on account of his war wounds. He stayed there until August 1865 when he traveled to Missouri in search of a new community. He stopped briefly in Macon, Missouri and moved on to St. Joseph, Missouri, where he settled for a year, trying to set up in business in his pre-war trade as a shoemaker. Before the end of 1866, he was back in Macon, the town in which he spent the rest of his life. He established a shoemaking shop there. In August 1871, George and Emeline divorced. On January 2, 1872, he married Elizabeth Trew (born December 13, 1843 in Ohio). George and Elizabeth had five children (Marion Cecil, 1872; Anna Tessora, 1874; Minnie Myrtle, 1876; Allie Pearl, 1878; Elizabeth Georgette, 1879). Anna and Allie died in their first year, but the others survived, Elizabeth until 1972—through all the world wars and the walks on the moon.

Yuncker pursued his livelihood as a shoemaker as long as old wounds allowed. He hired Gottlieb Schneider as an assistant, and Schneider took on more and more of the work. In 1882, Yuncker sold Schneider his shoemaker's shop. Yuncker received some pension increases for his wounds and rheumatism as his disabilities increased and his strength declined: 8/18 disability for the wound to his thigh (with damage to the sciatic nerve), 2/18 for the wound in his right arm (where the bullet still lodged), 2/18 for his destroyed finger, 0/18 for the shell wound to his butt. For a time, Juncker augmented his income by serving as both city and township tax collector. He came to use a cane more and more. In his last years, he could function only with assistance, having become nearly blind and nearly immobile.

On April 27, 1925, George Yuncker, having been shot full of holes at Chickamauga sixty-one years earlier and having been discharged from the Fifty-First Illinois on account of those holes, died of old age in Macon, Missouri, at the age of 91 years, 9 months, and 14 days. He was buried in Macon's Oakwood Cemetery just to the west of Pearl Street.

| The Yuncker Line in Oakwood Cemetery, Macon, Missouri The picture immediately below shows the entrance to Oakwood. The picture, second below, shows the seven stones. George Yuncker's is the middle of seven Yuncker stones. There is no large family stone; instead there seven stones, just alike, the last being placed in 1972 for Yuncker's daughter Elizabeth. |

|

|

|

|

|

Above: The George Yuncker stone. Right: The Yuncker line from the opposite end into the opposite distance. Below: Looking across the stones of Yuncker and wife Elizabeth. |

|

|

|

Sources:

George Younker, Compiled Service Record, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's-1917, Record Group 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Chickamauga Casualty List, Regimental Books Fifty-First Illinois Infantry, Record Group 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D. C.

Juncker's Second Corporal Document, George Younker Papers, C2100, Western Historical Manuscript Collection-Columbia, MO.

Death certificate, Missouri State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

George Yuncker, Pension File, Records of the Veterans Administration, Record Group 15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Regimental Hospital Records, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Phyllis E. Mears, ed. Mears Obituaries, Four Volumes. Decorah, Iowa: Anundsend Publishing Co., 1987-92. Thanks to the staff of La Plata Public Library, La Plata, Missouri for making the Mears obituaries available.

History of Randolph and Macon Counties, Missouri: Written and Compiled from the Most Authentic Official and Private Sources, Including a History of Their Townships, Towns and Villages, Together with a Condensed History of Missouri, a Reliable and Detailed History of Randolph and Macon Counties, Their Pioneer Record, Resources, Biographical Sketches of Prominent Citizens, General and Local Statistics of Great Value, Incidents and Reminiscences, St. Louis: National Historical Company, 1884.

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Washington D.C.

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, Washington, D.C.

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Ninth Census of the United States, 1870, Washington, D.C.

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Tenth Census of the United States, 1880, Washington, D.C.