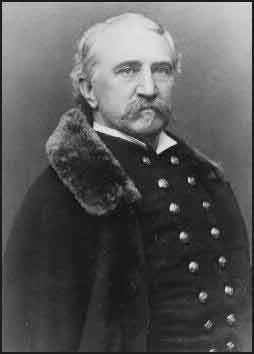

Colonel Luther P. Bradley

Colonel Luther P. Bradley Colonel Luther P. Bradley

Colonel Luther P. Bradley

Luther Prentiss Bradley was the first lieutenant colonel of the Fifty-First Illinois Infantry.

Before the War. Bradley was born on December 8, 1822 in New Haven, Connecticut. He was the youngest of 13 children. Until 1855, Bradley lived in Connecticut where he participated intensely in militia activities and developed a foundation in things military. In 1855, he moved west to Chicago. He worked for the firm of F. Munson, stationers and booksellers, in downtown Chicago.

Bradley was involved in the pre-war militia building activities in Chicago, especially as it became apparent that war might be in the offing. In August and September 1861, those activities transitioned into the building of the Fifty-First Illinois Infantry volunteers. Gilbert Cumming was the first colonel of the regiment; Bradley was lieutenant-colonel. See Formation of the Regiment on these pages.

Civil War Career. In the autumn of 1862, with the resignation of Colonel Gilbert Cumming, Bradley became colonel of the regiment, officially on October 14, 1862. But already by May 1862 he was in effective command of the regiment as Cumming was absent sick. He was in effective command of the brigade of which the Fifty-First Illinois was a part as of December 31, 1862 at the Battle of Stone's River. Bradley was in command of the brigade, consisting of the Twenty-Second, Twenty-Seventh, Forty-Second, and Fifty-First Illinois regiments, through the Battle of Chickamauga in September, 1863.

National Archives Photo

National Archives PhotoHis men knew him as even-handed and fair-minded, concerned for the welfare of his soldiers, not interested in the accoutrements of command as avenues of personal aggrandizement, not using office to push privates around. He was not mild-mannered; he was effective as a disciplinarian. He gained the respect of his men and his command superiors. There was no hot air to him. He made little military show and would not expose his men needlessly to danger but only for the military demands of battlefield situation. He knew when to exercise personal bravery as a tool of command as in the final charge of the Fifty-First and Twenty-Seventh at Stones River and, to take another example, when bringing his brigade into the conflagration in Viniard's Field on September 19, 1863. Two horses were killed under him at Stones River. He was wounded twice, shot clean through the hip and in the shoulder, within moments at Chickamauga. On October 2, Bradley in Louisville recovering and on his way to Chicago and then east to his family, wrote to his mother, "The wound in my hip is doing finely, and I can already walk pretty well with a crutch and cane. My arm scarcely troubles me at all, though I suppose the ball is still in there." In early November 1863, a local newspaper reported him back in New Haven recuperating from Chickamauga, a ball having passed "entirely through his body". Bradley returned to the Fifty-First in January 1864 just after many of its men had reenlisted and the regiment was on the verge of returning to Illinois for its 30-day reenlistment furlough. During that furlough Bradley oversaw the recruiting efforts of the officers of the regiment. When the regiment returned to the front, shortly before the 1864 Georgia campaign began, it had over 80 new members.

After Charles Harker was killed at Kennesaw Mountain on June 27, 1864, Bradley again acceded to the command of the brigade of which the Fifty-First was a part. He was promoted Brigadier General, U. S. Volunteers, on July 30, 1864.

Bradley was wounded again at Spring Hill, Tennessee on November 29, 1864, the day before the Battle of Franklin. The Spring Hill wound was a nasty wound, a bullet to the shoulder joint, and healed more slowly than his Chickamauga wounds. In early spring Bradley rejoined his brigade, but the wound was still an aggravation. Emerson Opdycke wrote to his wife on May 10, 1865, "[Bradley's] arm is still sore and painful and he can use it but little." Bradley resigned from the volunteer army in June, 1865. His old regiment was at that time moving toward Texas to spend its last few months there monitoring Napoleon III in Mexico.

After the Civil War. Bradley returned to Chicago and took up his old business. He soon however took a lieutenant colonel’s commission in the regular army. In 1868, Bradley married a Chicago woman Ione Dewey. They had two sons.

For the next twenty years Bradley commanded forces engaged in warmaking and peacemaking with Native Americans in Montana, Dakota, Arizona, and New Mexico. (Bradley's autobiographical sketch, written in the early 1880s, details his military career.) In 1876 and 1877 Bradley was first in command of the District of the Black Hills and then, headquartered in Omaha, in charge of surrendered formerly hostile Sioux Indians. A year after the Battle of Little Bighorn, the Federal government and the army had almost completed the pacification of Lakota Indian bands, with special interest in regard to the band led by Crazy Horse, the victorious warrior of Little Bighorn. Crazy Horse had already surrendered the autonomy of his Lakota band. He had become a non-commissioned officer of the United States Army. It was intended that he visit Washington D. C. to meet the president, but Crazy Horse became suspicious of white men's plans for him, delayed the visit to Washington, and moved his band toward the open plains. General George Crook's men, in conjunction with Indian leaders who opposed Crazy Horse' independence, met clandestinely in council and laid plans to lure Crazy Horse into a trap where he would be taken captive, thus obviating the need for further negotiations. Bradley learned of the machinations and privately asked William Garnett, the half-Lakota interpreter at the planning council, to inform him qw to what was to transpire. When Garnett confirmed Bradley's suspicions, Bradley said (in Garnett's paraphrase) that it was "too bad to go after a man of the standing of Crazy Horse in this matter in the nighttime without his knowing anything about it. They ought to do this in broad daylight. There are plenty more soldiers after we are gone. The life of Crazy Horse is just as dear to him as my life is to me" (quoted in Hardorff, 41-2). Bradley countermanded the orders and reset them for the next day. But, night or day, the sequence of chicanery that would lead to Crazy Horse' death was already in motion.

Bradley retired with the rank of full colonel in 1886. He lived out his retirement years in Tacoma, Washington until his death in 1910. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery (Section 2).

Bradley, Old, in Tacoma

Bradley, Old, in Tacoma

Sources:

William F. Prosser, A History of the Puget Sound Country, Its Commerce and Its People, New York: Lewis Publishing Company, 1903, 192-4.

Luther P. Bradley, Compiled Service Record, Record Group 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

The Willimantic Journal, Willimantic, Connecticut, November 9, 1863.

Luther Bradley Papers, United States Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Glenn V. Longacre and John E. Haas, eds., To Battle for God and the Right: The Civil War Letterbooks of Emerson Opdycke, Urbana and Chicago: The University of Illinois Press, 2003, p.291.

Richard G. Hardorff, ed.,The Death of Crazy Horse: A Tragic Episode in Lakota History, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

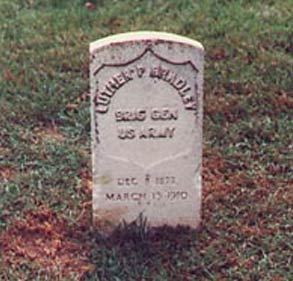

Bradley's Gravestone

Bradley's Gravestone

Section 2, Grave 172-1

Arlington National Cemetery

Photo by Joe Ferrell