Sergeant James Sedgwick

Sergeant James Sedgwick Company B

Sergeant James Sedgwick

Sergeant James Sedgwick

Company B

James H. Sedgwick was born September 4, 1840 in Coshocton County, Ohio. The family moved to Illinois in 1844. Sedgwick attended Oberlin College and then studied law in Chicago, and was admitted to the bar in July, 1861.

On August 15, 1862, Sedgwick enlisted in Company H of the One Hundredth Illinois Infantry. He was immediately appointed first sergeant of his company. From that point on, Sedgwick's military career, as revealed by his military records, was a rocky one in a non-ordinary way. His records state that he deserted from the regiment in the face of the enemy at Stones River on December 31, 1862, was "not apprehended". This was beyond the pale and Sedgwick was reduced to the ranks by his regiment, on January 13, 1863. His records for January/February, 1863 list him as sick in hospital at Nashville. Then, according to his service records, he deserted a second time—this time from a convalescent camp at Nashville on April 12, 1863.

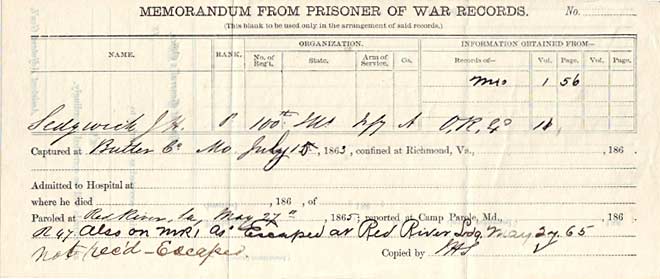

We next hear of him captured by the enemy in Butler County, Missouri on July 15, 1863. This is three months later and 250 miles to the west, in southeast Missouri. One might ask what was Sedgwick doing in Butler County, Missouri. Following his capture, he was confined at Camp Ford in Tyler, Texas for almost two years. His records bear yet one more tiny mystery. The records state that he was both released on parole at Red River, Louisiana on April 27, 1865 and that he escaped from Red River Landing on the same day. It seems that Sedgwick did not wait for formal parole paperwork, was not "receipted for", and immediately began to work his way north. Or, perhaps authorities did not know Sedgwick had escaped until they tried to parole him.

At any rate, the One Hundredth Illinois hadn't seen Sedgwick since December 30, 1862 and only the adjutant and other officers knew that he was in hospital and convalescent camp at Nashville after his "desertion". The regiment forgot about Sergeant-busted-to-Private Sedgwick. But then, out of the blue, on June 10, 1865, Sedgwick presented himself to the One Hundredth Illinois at Camp Harker, outside Nashville—where the Fourth Army Corps, including the One Hundredth and the Fifty-First, were resting from their labors. The officers of the One Hundredth were less than delighted to see him; he had after all deserted the regiment twice, and one of those times as they prepared to go into battle—and, most importantly, they were wrapped up in the final red tape of mustering out (June 12, 1865)—along with many other regiments—and preparing to travel north to Chicago to be paid off. They hardly wanted to pause and figure out what to do with Sedgwick. They took the easy way out; they unloaded him on the Fifty-First with a detachment of their other soldiers who had time to serve before muster-out. James Boyd, who was in command of the regiment at the time, explained at Sedgwick's court martial:

The detachment of the 100th Ills. Inf., which were assigned to the 51st Ills. Inf. Vols. under the order [Special Order 104, 2nd Division, 4th Army Corps, June 7, 1865] transferring all troops whose time of service had no longer to serve than September 30/65 - the transfer was made a day or two before the 51st regt embarked for Johnsonville enroute for New Orleans, La. both the Adjutant and myself (who was commanding the regt) hesitated to receive the soldier considering that he was not properly transferred, not having sufficient papers with him, and I have no doubt in my mind that the cause of the accused standing in this position towards his fellow soldiers was undue haste on the part of the officer commanding his company in the 100th Ills. Inf. But, under our orders we had no other alternative than to receive him, incomplete as the papers were.

Sedgwick was transferred on June 10, 1865, as a private, to Company B of the Fifty-First Illinois, that is, on the day he returned to the One Hundredth he was transferred out of it to the Fifty-First in compliance with the three-day-old Special Order 104. Well might Boyd complain of "undue haste". Lieutenant Charles Russell of Company H of the One Hundredth (Sedgwick had been his superior during the regiment's first four months) scrawled out the "descriptive list" for Sedgwick to present to the Fifty-First (a descriptive list was that formal document that accompanied a soldier at all transitional moments of his military career). The one Russell prepared read, "Said named soldier deserted from the battlefield in the face of the enemy Dec 31st 1862 at Stone River Tenn and returned to his command June 10th, 1865." (There must have been an icy moment in Tennessee if Russell handed the descriptive list to Sedgwick directly.) The records of the One Hundredth did record more of Sedgwick's doings (e.g. his stay in Nashville hospitals and convalescent camps), but whether they were available to Russell or not is unknown to us; perhaps they had already been packed up and were in trunks ready to ship north. The descriptive list seemed to damn Sedgwick but actually helped him since the two and one-half year gap in its dates made it almost useless in assessing Sedgwick's whereabouts and doings.

On July 9, along with a number of other soldiers (mostly from the Fifteenth Missouri Infantry), he was put under arrest for desertion, as brigade commander Joseph Conrad cleaned house. But, already Sedgwick's luck had begun to turn; his new regiment saw his past two and a half years—the time intervening since Stones River—in a new light; Sedgwick began to speak in his own defense with the men and officers of his new regiment. And, although formally under arrest, he was on duty with his new company. A note in his file speaks of his red-tape vindication: "Reported and retained improperly as a deserter, tried and acquitted by Gen C. M. [general court martial]." Retained improperly. So, where was Sedgwick on December 31, 1862? and, what was he doing getting captured in Missouri in the summer of 1863? Had he run away from home a second time?

At the general court martial, which sat to adjudicate a number of cases in August-September, 1864, while the Fifty-First was in its last camp, Camp Irwin, Texas, the prosecution presented two pieces of evidence against Sedgwick. The first was Boyd's statement quoted in full above. The second was the "descriptive list" written by Charles Russell. Clearly, the prosecutor was merely going through the motions; he never tried to make a case against Sedgwick.

Sedgwick presented two items in his defense—he had no others. The first was a statement from Dr. Adolph Heise, the regimental surgeon of the One Hundredth Illinois. Heise stipulated, "James H. Sedgwick of Comp H, 100th Regt of Ills. Vol. Inf., having reported himself, on or about the 31. of December 1862 (during the battle of Stone River) as sick to the Division field Hospital, at that time under my charge. I certify that I examined this soldier and found him to be unfit for duty and ordered him to be sent, with many other transportable sick soldiers, to Nashville, Ten., in accordance with an order previously received from the Medical Director of the Department." And, thus, Sedgwick began his stint at Nashville hospitals and convalescent camps, while his company and regiment jotted him down as a deserter. The second item Sedgwick presented was his own written statement; it said:

Gentlemen: I was captured in Missouri, about 25 miles below Cape Girardeau, while going home from the convalescent camp of Woods' Division in Nashville sometime in the latter part of June or the first of July 1863. I was taken by bushwhackers who carried me to Col. Kitchen's command then operating in northern Arkansas. Col. Kitchen sent me on to Little Rock where I arrived about the last of July. From there I was sent southward via Arkadelphia and Washington, Ark. and Clarksville, Tex. to Bonham, Tex. From thence I was sent to Tyler, Tex. about the 1st of January 1864. I remained at Camp Ford prison near Tyler until on or about the 3d of May 1865 when I made my escape. I arrived at Little Rock on the 1st of June, 1865, reported to the Provost Marshl and was furnished with transportation to my Reg. the 100th Ill, where I reported the 10th of June 1865. While in captivity I was clothed in rags without adequate means of cleaning myself or clothes untill sometime in the fall of 1864 when our government sent us through some clothes and blankets when I drew a part of a suit but not enough to keep me warm through the winter in the open brush shed, which was called a hospital, where I was sick with the scurvy from about the 1st of October until I escaped. I drew another partial suit from our government which came through sometime in March 1865. Our rations were from a pint to a quart of corn meal per day, 3 to 6 oz's bacon or 3/4 lb to 1 lb beef per day and a little salt once in five days. While in the hospital I only got half rations. Some of our guards were civil to us, others would insult and shoot all of us as they got a chance. Their commanders never punished any of them for abusing or killing Yankees. Some of the prison commanders seemed kind to us while others were very severe and would punush us cruelly for trying to escape or other misdemeanors as they were called. We had 5 different commanders while I was in prison at Tyler, 2 of them comparativesly good, the other 3 villainous.

On September 21, Brigade Commander Joseph Conrad upheld the decision of the court martial and ordered, "Prisoner will be released," from his being held under arrest-of-sorts. Sedgwick was mustered out with the last of the Fifty-First on September 25, 1865, honorably discharged—and a sergeant once more, having been promoted on September 1 while the verdict of his court martial was offically pending but unofficially was a foregone conclusion. To his grave, Sedgwick was of the Fifty-First Illinois, the regiment that first grudgingly accepted him—"we had no alternative"—gave him a hearing, formally and informally, put him on duty during the last three and one-half months of his military life, and saw him through to acquittal, promotion to sergeant, and honorable discharge—discharged honorably, rather than under a cloud.

On July 10, 1866, Sedgwick married Maria B. Merritt in Maria's home town, Ross Grove, Paw-Paw Township, DeKalb County, Illinois. Sedgwick and Maria had four children. Sedgwick died on January 26, 1909. He was buried in Springdale Cemetery in Peoria, in the Mount Hope section of the cemetery, Lot 2878. Maria survived him until January 27, 1933.

Below: The prisoner-of-war slip from Sedgwick's service records:

The following biographical sketch is taken from a book published in 1890, Portrait and Biographical Album of Peoria County, Illinois: Containing Full Page Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens of the County (full title below).

James H. Sedgwick. Among the prominent law firms of Peoria County, may be properly mentioned that of Bailey & Sedgwick. As Mr. Bailey is principally engaged in banking and a large loan business, the legal transactions of the firm are conducted by Mr. Sedgwick, the subject of this sketch, who has been practicing in the city of Peoria continuously for the past fifteen years. He is fifty years of age, having been born September 4, 1840, and is a native of Coshocton County, Ohio, the son of Samuel and Ruhama (Knight) Sedgwick, of whom Ruhama, the mother, is still living in Sandwich, Ill. Samuel Sedgwick is a native of Connecticut, a descendant of Robert Sedgwick, one of Cromwell's generals, and at his death, Governor of Jamaica. It is a family that has produced lawyers, writers, soldiers and statesmen. Among them were Judge Theodore Sedgwick of Massachusetts, Catharine Sedgwick, the authoress, Maj. Gen. Sedgwick on whom Gen. Grant relied so implicitly, and Maj. Sedgwick who was with Washington at Valley Forge.

The father of our subject was reared to manhood in his native state and was educated for the profession of a physician, which he followed first in Oneida County, N.Y., where he married, and afterward in Coshocton County, Ohio. About 1844 he came with his family to Kendall County, in this state, but only lived three years thereafter, his death taking place in 1847. Young Sedgwick was reared by the mother, and after leaving the common schools became a student in the famous Oberlin College, Ohio, where he pursued his literary studies. He was admitted to the bar in in July, 1861, after a course at Chicago Law School under the direction of Judge Booth. He commenced the practice of his profession in Sandwich, this state, but after the outbreak of the Civil War, entered the Union Army. He participated in several active engagements, was captured by the rebels and taken to Tyler, Texas, where he was confined two years and then succeeded in making his escape. He worked his way North to the Union Lines in Arkansas, where he succeeded in due time in rejoining his regiment, and remained with it until the expiration of his term of enlistment shortly afterward. He was honorably discharged as a Sergeant, Company B, Fifty-first Illinois Veteran Infantry, and bears on his person the scars of a faithful and exceedingly trying military experience.

Returning now to Sandwich, Ill., Mr Sedgwick returned to his law practice, but subsequently removed to Sycamore and in partnership with Judge Lowell followed his practice two years. We next find him in the city of Chicago, where in 1873, he associated himself in partnership with O. J. Bailey, and two years later removed to Peoria, where they successfully followed the profession in which they have attained a good reputation.

Politically, Mr. Sedgwick, although mingling very little with public affairs, is a decided Prohibitionist, being one of the organizers of the party in this county and their nominee for congress in 1888. But while believing that the total prohibition of the saloon is the true policy of the State, he is by no means a fanatic. He is liberal and progressive in his ideas, the friend of education and reform; he is one of the early members of the Law Library Association in which he has held all the offices, and is now President, being elected in the spring of 1889. This library is a very complete one, comprising fifty-five hundred volumes, furnishing an invaluable store of information to those following the legal profession.

Mr. Sedgwick is a valued member of the Peoria Scientific Society, and his public addresses before that society are highly appreciated. The calls on him for addresses before other associations and on other occasions are frequent. His hearers are wont to remark that "Mr. Sedgwick has always something to say worth listening to." In the National Bar Association he is for the third time Chairman of the Committee on Legal Education and Admission to the Bar, and his annual reports on that subject are anticipated as an event of the session.

On the 10th of July, 1866, Mr. Sedgwick was joined in wedlock with Miss Maria B. Merritt, daughter of William J. Merritt, a prominent pioneer of DeKalb County. Of this union there have been born four children who are living. The eldest son, Howard, is a practicing physician of Peoria. William C. is a hardware merchant of this city and located on Main Street; Philip and Edna remain with their parents, attending the city schools. The family residence is pleasantly located on the East Bluff portion of the city and is frequented by its cultured and intelligent people. Mr. and Mrs. Sedgwick have ever a hearty welcome for progressive people, those who think and have definite original ideas, whether or not they agree with them.

Mr. Sedgwick held several public offices in the first part of his career, while retainers were scarce and fees small. He consented at one time to act as a Justice of the Peace, afterward for a short time, to fill an interregnum, was County Attorney of DeKalb County. Then he was elected City Attorney of Sandwich, but refused to qualify. He holds that a man who has a good private business is not wise to sacrifice his independence for a public office, and that independence of thought and action is worth more than any office.

Sources: