|

Lieutenant Frederick Grabbe

Company G

Frederick Grabbe was born in Germany (Kingdom of Hanover) on October 16, 1842 and migrated to the United States with his parents when he was three years old. His father died while Frederick was quite young; his mother remarried. Frederick grew up on a farm in Fremont Township, Lake County, Illinois. He was living there at the time of his enrollment as a private in Company G of the Fifty-First Illinois, in October 1861. He was nineteen years old at the time.

He was continually present with the regiment until he was wounded in the left arm at Chickamauga. He escaped capture, unlike many of his comrades, and convalesced at one of the military hospitals in Nashville. The wound affected him for the rest of his life, causing him to favor his left side, which always appeared lower than his right. He was back with the regiment by December, 1863.

Grabbe reenlisted as a veteran in February 1864 with many other members of the regiment. (View his reenlistment papers). He was promoted to the rank of sergeant on February 8, 1864 and promoted orderly sergeant on July 1, 1864. He was promoted First Lieutenant on February 25, 1865.

After the war Grabbe settled in the town of Libertyville, Illinois. On December 25, 1872 he married Elizabeth Gray (pictured at right), a native of the State of New York. They had three sons: George, Charles, and Maurice. The 1880 U. S. census shows Grabbe earning his living by keeping bees. |

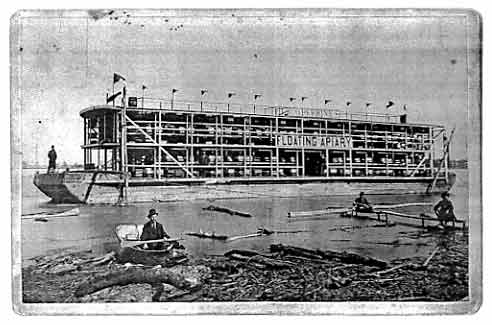

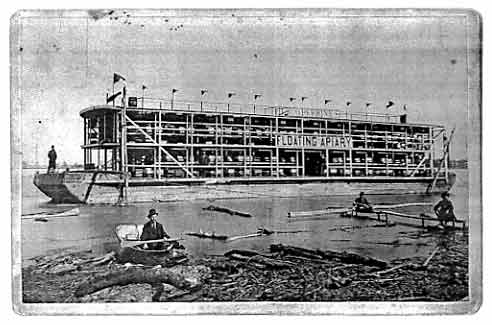

| Keeping Bees. Grabbe was no ordinary beekeeper. His bees were imported Italian bees and hybrid bees. The bees and the honey were sold in Chicago (on Kinzie Street, opposite the Chicago Northwestern depot)and directly from the apiaries at Libertyville, Illinois and in St. Charles County, Missouri. C. E. Carroll wrote, in a sketch of Grabbe's entrepreneurial ventures, "He could see opportunities that no one else recognized and was never afraid to try new things." One of his ventures consisted of, as Carroll put it, "persuadiing bees to make honey in the winter." Grabbe and a Civil War comrade, Charlie McDaniel, equipped a large flat boat with beehives (photo shown here). In late fall, when bees ceased their honey-making endeavor in the upper Midwest, the partners drifted down the Mississippi, floating by night and tying up by day. The bees continued their work in the continuing warm weather—as the boat slipped further south—and returned to the boat's hives before nightfall. The bee-keeping and honey-making proceeded beautifully—until the boat drifted into the lower south where wharves were stocked with barrels of sugar and molasses. The bees, fickle, forsook their boat-home for the sweeter pastures of the sweets on the wharves. Grabbe and McDaniel, nearly beeless, sold their beehive boat and went home to Libertyville. This was not the end of Grabbe's beekeeping business—only the closing of its floating branch office in the deep South. |

|

Milling Flax. Lake County farmers, after the Civil War, began raising flax, and Frederick Grabbe built a steam-powered flax mill to grind the seeds and press the flax oil for market. To keep his steam engine busy year round, Grabbe built a saw mill—the primary business of which was making cheese boxes for the Libertyville cheese factory. Grabbe had yet another use for his steam engine and soon had a feed mill in operation that ground feed for Lake County farmers.

Bottling Water. Libertyville, like Fremont Township where Grabbe grew up, is located in Lake County, which borders Wisconsin on the north. The village is a little over 30 miles north of Chicago and seven miles west of Lake Michigan. Butler Lake lies to the west of Libertyville, Minear Lake to the northeast, Liberty Lake to the southeast. The Des Plaines River cuts through Lake County, from its source in southern Wisconsin, generally flowing north to south but on a winding course. The river, running through forest preserves, creates "a nearly continuous greenway though all of Lake County." The peculiar geologic structures that filled Lake County with lakes offered Grabbe his next entrepreneurial opportunity. Early on, the well water along the river was known for its special qualities. C. E. Carroll wrote:

The earliest settlements were along the west side of the Des Plaines and it was the endeavor of each settler to include a portion of the river in his claim to insure water for his stock and we find all of the early farms were laid out in long narrow tracts with the east or west bounds at rights angles to the river at the particular point and this accounts for the fact that our present township maps look like jigsaw puzzles, for every man was his own surveyor at first and the river was far from straight. For household use the farmer dug a well and he usually found a good supply of water at less than twenty feet below the surface. Most of this water was clear and "sweet". That is it had no pronounced taste or odor but in some places, especially on the east side of the river, there were springs and wells of strong mineral content, principally sulphur, which gave the water a disagreeable odor and a milky appearance when drawn into a large vessel. This however, was believed to be highly beneficial to humans and to stock and persons soon became accustomed to the taste and odor and even preferred it to the "sweet" water.

| Communities along Lake Michigan—Chicago and the neighboring lesser towns—drew their drinking water from Lake Michigan but it was becoming contaminated by the sewage draining into it, the arch offender being Chicago. Starting in 1880, when fully involved in beekeeping and flax and grain milling, in partnership with Walter Cast Newberry, Grabbe started to develop a business in good natural Lake County water.

Wells drilled in Libertyville hit cool underground reservoirs at no more than 60 or 70 feet deep. The water welled to the surface; no pumping was required. The water was so cool that some citizens routed it to sinks in their houses where it was used to keep butter and other perishables cool. Grabbe hit upon the idea of bottling the water and creating a market for it in Chicago and its suburbs, where people were thirsty for good water. He drilled a well on his own Libertyville property and had the water chemically analyzed by the University of Illinois; its purity was confirmed. Grabbe and Newberry formed a company, called "Abana Spring", for bottling the water.

As for the name—Abana Spring (logo at right)—C. E. Carroll wrote, "The well on Newberry (street) was called Abana Spring, supposedly named after a famous well in the Holy Land, though it may have been named for an ancient health resort in the province of Padua in Italy which was famed in early Roman times for its white sulphur springs whose waters were believed to cure skin diseases." Indeed, there is a spa village named "Abana" in Padua. But, also indeed, there are references in ancient scriptures (II Kings) to Abana, which meant "gathering of waters". No doubt Abana in Padua derived its name from this "gathering of waters", and so did Grabbe when he gathered the waters of Libertyville and put them in bottles. |

Walter C. Newberry, Grabbe's Partner

Newberry (1835-1912), son of a well-to-do New York family, enlisted, in 1861, as a private in the Eighty-First New York Infantry and subsequently transferred to the Twenty-Fourth New York Cavalry where he rose to the rank of colonel. After the war he was the mayor of Petersburg, Virginia, then for four years superintendent of public property for the State of Virginia. He moved to Chicago in 1876. For two years, 1891-1893, he served in the U. S. Congress, elected as a Democrat by his Illinois district. He did not stand for reelection. He was the nephew of Walter Loomis Newberry, the founder of the Newberry Library in Chicago. Walter C. Newberry lived in Chicago but owned land and kept fine horses in Libertyville (Newberry Avenue in Libertyville was named after him). Grabbe pastured and tended Newberry's horses—this was apparently the initial contact between the two men. Newberry subdivided some of his Libertyville property, and Grabbe sold some of it for him. Some of the lots fell to Grabbe himself. They had collaborated on business, on the flax mill as early as 1881, and soon they were exploring water possibilities together. |

The containers were shipped to Chicago for distribution and sale by an agent, C. F. Greenwood, in the city on LaSalle St. Newberry used his railroad connections to get the containers shipped to Chicago. A 1909 brochure listing and describing Libertyville's leading businesses and citizens said, "The price is $1.00 for two demijohns, ten gallons, delivered free at residence or office in Chicago by the United States Express Company. The express company will return the empties." An advertising card said, "Abana Spring water is notable in this respect (being free from contamination) as it has been analyzed at the University of Illinois with the result that no organic or objectionable matter was found therein, such a circumstance being very rare in the experiences of analytical chemists. But the analysis shows that this water contains 29 795/1000 grains per gallon of healthful mineral salts; this slight impregnation gives it vitality and other qualities which noticeably benefit its users."

Grabbe in His Prime |

|

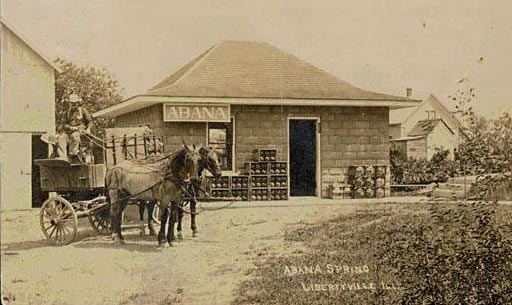

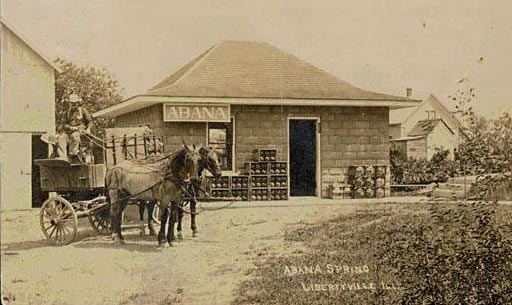

The building (with the ABANA sign) shown on this postcard photograph was built right over the outlet of Grabbe's bottling well. C. E. Carroll wrote, "The water flowed continually from a curving pipe into the sunken basin and drained away and needed only one man to push the demijohns under the pipe and to cork them when full." Around 1903, Grabbe began shipping gallons of water, in boxes of 6, to grocery stores in Chicago and suburbs. In the picture, to the right of the door, you can see nine five-gallon demijohns of water. To the left, you see a number of gallon jugs in their six-packs. One of Grabbe's six-gallon packs of water sold for sixty cents. (The photo postcard dates back to 1910.)

(At left: Grabbe, Aging, in Libertyville)

Near Libertyville, near the Rockland Road bridge, a sulphur spring flowed from the bank of the Des Plaines River. Native Americans had long used the waters from the spring for healing purposes. Analysis showed that the water did indeed have healing qualities. Grabbe and Newberry began bottling the sulphured waters. They sold this as "Vital Water". It had to be bottled in brown glass because heat from the sun would cause the naturally occurring chemicals to react and even explode. Next, Newberry and Grabbe explored the idea of creating a health spa at Libertyville centered around healing springs. Carroll wrote that they "brought in Army engineers to survey the situation at the Sulphur Spring but their verdict was that it would entail an expenditure of some $200,000 to develop the spring properly. The whole course of the dirty river would have to be changed for one thing to divert it from the spring." Grabbe and Newberry dropped the idea. They filled their gallons and demijohns and sold them throughout Chicago and across its northern suburbs. Grabbe prospered; Newberry hardly needed to.

Eventually, after 30 years of welling up to the surface, the first Abana Spring began to run dry. Grabbe discovered another well of such water on Park Place in Libertyville and bought property there for a second Abana Spring. It is the second Abana that is shown in the photograph above. The town's "Industrial News" for August 14, 1909 wrote, "One of the sights of Libertyville is the Abana flowing spring, located adjacent to the public park. Abana, one of the purest and most salutary spring waters known, famous for table use... the water flows clear and sparkling from seventy feet below the surface." The sparkling water welled up 650 miles and 47 years distant from the smoky Georgia terrain at Chickamauga Creek where Frederick Grabbe was shot in the shoulder, and where wounded and dying enemies lay between the lines all the night of September 19, 1863, pleading for water.

Grabbe died on October 14, 1915. He was buried, with Masonic services at graveside, at the Ivanhoe Cemetery—in Fremont Township where he grew up. His mother had been buried in the same cemetery. The Abana Spring business ceased at the time of Grabbe's demise. The growth of thirsty business and industry in Libertyville lowered the water table and brought an end to Grabbe's springs.

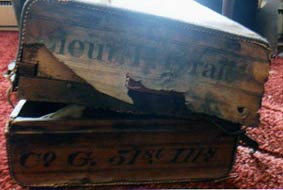

Photos at Right. Upper left: the oak family trunk—the G-r-a-b-b-e carved into the wood still discernible today—that accompanied Frederick and his parents from Hanover to Illinois. The key, says great-granddaughter Elizabeth Iversen, still works.

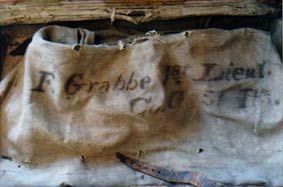

Three views of the valise that Lieutenant Grabbe carried during the war. Lower left: the valise itself. Upper right: the valise itself viewed from one of its end. Lower right: the canvas cover that covered the valise. The valise is at the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society, Libertyville, Illinois.

Sources:

Grabbe in his prime photograph, elderly Frederick Grabbe photograph, Abana Spring photograph, Elizabeth Gray Grabbe photograph, oaken chest photograph, valise photographs, Abana Springs logo, obituaries, family papers, courtesy of Elizabeth Grabbe Iversen and Katherine Grabbe Luetkemeier, great-granddaughters of Frederick Grabbe.

Genealogical research by William Edward Henry.

Photograph of Grabbe in uniform, used, with thanks, through courtesy of unknown contributor.

Frederick Grabbe Compiled Service Record, 51st Illinois Infantry, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's-1917, Record Group 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

C. E. Carroll, "Frederick Grabbe," Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society typescript (#2179) circa 1950s, on file in family archive of Elizabeth Grabbe Iversen.

C. E. Carroll, "Spring Water," Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society typescript on file at Cook Memorial Public Library, Libertyville, Illinois, circa 1950s.

About the Des Plaines River: http://chicagowildernessmag.org/issues/summer2000/IWdesplaines.html